Executive Summary

Conflict gold remains a major obstacle to peace and a driver of the black market economy in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. It provides a significant source of income to armed actors, from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) rebel group and Mai Mai Sheka factions to Congolese army commanders, whose troops kill and sexually abuse civilians with impunity, and several of these armed groups trade gold for weapons and ammunition. While progress has been made on reducing armed groups’ profits from three out of four conflict minerals in Congo—tin, tantalum, and tungsten—gold continues to finance armed groups and corrupt army officers and officials in Congo and the region.

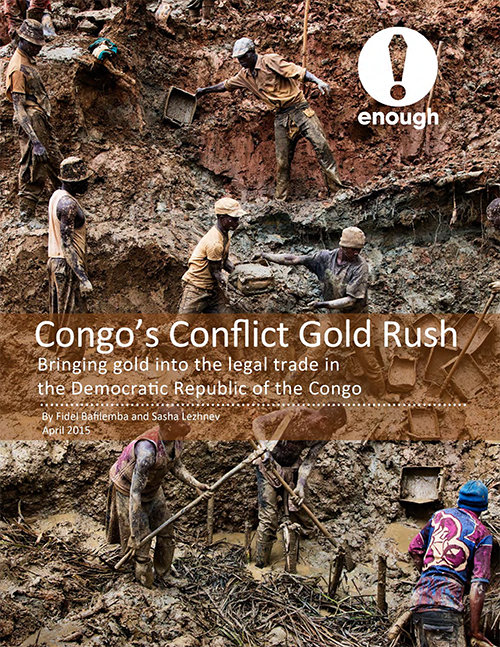

Addressing the trade in conflict gold will not be easy, but with a series of targeted interventions it is possible to reduce the scale of the problem and cut into armed groups’ profits. According to U.N. experts, an estimated 98 percent of gold produced by artisanal miners in Congo—8 to 12 tons worth roughly $400 million–is smuggled out of the country. Artisanal miners in Congo work by hand with pick-axes and shovels, largely illegally, due to an over-regulated, corrupt system put in place by government officials and army commanders who take sizeable cuts from the trade. Gold is easy to hide because of its high value in small quantities—half a million dollars’ worth can fit in a briefcase—and a smuggling system has been in place for decades. The illicit conflict gold supply chain moves mainly through Uganda and Burundi, where military officers allegedly also profit, and then much of the gold arrives in Dubai, a major global gold trading and refining hub that has its own smuggling loopholes.

Recent positive developments are beginning to offer encouragement for altering the conflict trade. There is a new, growing recognition in Congo and by an increased number of global gold industry companies that the conflict gold problem must be addressed now. Based on international due diligence guidelines, gold refiners and mining companies are now undergoing third-party audits by the London Bullion Market Association and associated programs focusing on conflict and high-risk issues. Sixty-nine refiners, including all of the world’s nine largest, have passed the audits so far. In addition, gold mines in Congo are beginning to be inspected by multi-stakeholder teams of government, civil society, and business representatives. Ten gold mines that met the criteria for being conflict-free have been validated so far, and 50 more are due to be inspected in the remainder of 2015. Armed groups such as the FDLR and others have been removed from some gold mines by Congo’s army, and some Congolese army officers have pulled out of a handful of mines reportedly because of local Congolese anti-conflict minerals campaigns and out of fear of being named and shamed in U.N. reports. There are also two industrial mining consortia producing conflict-free gold in eastern Congo: Banro and AngloGold Ashanti/Randgold Resources, which collectively exported 17.4 tons of gold in 2014 worth roughly $700 million, a major development over the past three years. But much more effort is needed to build a clean gold trade. Fifty-seven percent of miners in gold mines surveyed in eastern Congo still work under the control of armed actors, according to IPIS.

Policy reforms to address the conflict gold problem must begin with a wider vision that the Congolese state and its people can benefit from an increased legal gold trade in the formal economy, while corrupt actors in the current illicit system must face consequences for their actions. A shift in gold taxation policy in Congo and the region would help. Lessons from international attempts to control gold smuggling from the Philippines to Mongolia have shown that high taxes on gold only drive the trade further underground. Congo’s current overall gold tax of 13 percent —an enormous rate for gold compared to average rates of between 1 and 5 percent in other countries —is a major disincentive against bringing the trade into legal channels. Reduced taxes and improved artisanal mining regulations would help increase the volume of gold traded through the legal system. Initial estimates by the Enough Project show that Congo’s government would increase its revenue by 870 percent by lowering taxes and streamlining regulations on artisanal mining – from $230,000 per year in taxes to over $2 million. Mining communities would also benefit from an increased legal trade, as armed actors withdraw from mines and their revenue streams from the lucrative gold trade are reduced. The Congolese government must also implement its constitutional obligations to remit 40 percent of revenues back to the provinces, which would benefit communities. Unfortunately, Congo’s current loophole-filled implementation of the gold component of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) regional minerals certification process is stifling the legal gold trade and creating more incentives for smuggling.

Constructively, there is a flurry of new proposals from Congolese and international civil society, the Congolese government, and the gold industry on ways to address the problem—from miners’ registration programs to gold tracing schemes to increased inspections of gold mines. By identifying commanders in the conflict trade, the multi-stakeholder process to inspect and validate mines in Congo puts pressure on the government to remove armed commanders from mines, but the inspection process and needs more robust support. As a Congolese civil society activist told Enough, “[Conflict-free mine] validation gives pride to the people. It brings security to mines. Where the system is functioning, life is taking off—with new pubs, businesses, etc.”

Beyond mine inspections, there must be a serious anti-corruption initiative in Congo’s Mining Ministry, including prosecutions of corrupt officials and the consolidation of the five different government agencies that collect taxes on minerals. Furthermore, jewelers, investors, and other groups should signal increased demand for conflict-free Congolese gold and create a new, legal buying arrangement for it. As mines get inspected and validated, there must be a legal market ready to buy the gold that is certified as responsibly sourced. Otherwise, miners will be forced to sell through the illegal channels that benefit armed actors.

In addition, there is a need for robust livelihood programs for artisanal mining communities to accommodate shifts in the job market that accompany formalization of the gold trade. More than 100,000 Congolese miners and their families depend on the trade, and their lives will be harmed if their ability to support their families is undermined. Programs should include both projects to legalize mining and improve working conditions, as well as alternative livelihood projects such as small business, microfinance, and agriculture.

In addition to formalizing artisanal mining, more work should be done to increase responsible industrial gold investment in eastern Congo. Industrial mining companies can help limit revenues for armed actors operating in the informal market. For example, gold mines in South Kivu that were previously occupied by FDLR rebels are now certified conflict-free mines operated by the Canadian company Banro. The gold from those mines does not go to armed groups any longer. This is a challenging area to be sure, as industrial mining has a checkered past in Congo, as several regimes and some companies have exploited local communities, and risk is still high in Congo, and the world gold price is low. Industrial miners, foreign or Congolese, must operate in a transparent, responsible manner, including meeting high standards related to environmental protection, transparency, and community consultation. The Congolese government is currently reviewing dormant mining concessions, with 49 percent of mining titles in South Kivu and 41 percent of titles in North Kivu under review. Industrial miners and the Congolese government should also develop more constructive arrangements to work with artisanal miners.

Finally, criminal actors in the illegal trade that have acted as financial support networks for armed commanders for years should be targeted for sanctions and prosecutions. The U.N. Group of Experts has extensively documented and named certain criminal networks of Congolese armed actors and regional smugglers in Congo, Uganda, and Burundi, who are alleged to have committed crimes such as pillage and minerals trafficking. Furthermore, the U.S. and other governments should provide greater airport and customs scrutiny support to Uganda, Burundi, and other regional airports to help close smuggling loopholes. The Enough Project further recommends specific policy measures in the following areas.

Recommendations

- Suspend gold certification until it is credible. The U.S. State Department should urge Congo’s Mining Ministry to halt the issuance of ICGLR certificates for gold exports from Congo until key steps are taken that would make the process compliant with ICGLR standards. Those steps include the validation of a sizeable number of gold mines and the adoption of a viable traceability scheme for gold.

- Inspect gold mines. The European Union, as it moves forward on conflict minerals regulation, should provide funding to mine inspection missions to assess mines on conflict issues in Congo. The inspection process, currently led by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the German government, is one step to help get armed commanders out of mines. Relatedly, the Congolese Mining Ministry should designate more mines as Artisanal Mining Zones and allow mining cooperatives to apply for mining licenses.

- Set up a responsible gold investment fund. Socially responsible investors should set up a responsible gold fund for Congolese gold by partnering with jewelry retailers, fair-trade mining groups, civil society, refiners, local gold buyers, venture capital managers, and donor governments. Investors would provide the startup capital to pilot conflict-free projects and would earn revenues from increased productivity at artisanal and other mines. This would compete with the conflict gold smuggling network. Jewelry retailers and gold refiners should also commit to purchasing conflict-free gold from eastern Congo when available, following the lead example of Signet Jewelers.

- Enforce effective anti-corruption measures and reduce red tape. The U.S. State Department, USAID, the German government, the European Union, and U.N. envoys Said Djinnit and Martin Kobler should urge Congo’s Mining Ministry to begin a comprehensive anti-corruption initiative. The initiative should include prosecuting high-level cases of corruption and consolidating the government agencies involved in regulating the gold trade. The envoys should also urge ministry officials and provincial governors in eastern Congo to significantly lower the 13 percent overall gold tax rate. Finally, donor governments should urge Congo’s Centre d’Évaluation d’Expertise et de Certification (CEEC) agency to make its traceability program financially sustainable by making the fee for traders to use the program a maximum of 1 percent of the gold price.

- Set up sustainable miners livelihood programs. The U.S. Congress and the European Union should authorize funding for livelihood programs for artisanal mining communities, including microfinance for miners and alternative income projects and the reform of mining cooperatives. Jewelry retailers and electronics companies, and other metals companies should also contribute to mining community livelihoods initiatives.

- Conduct geological mapping. The World Bank should fund geological exploration of mining areas in the Kivu provinces of eastern Congo through a new mining support project and expanded support to the Cadastre Minier (CAMI) mining registry of the Congolese government. This would help open up other mines for responsible investment.

- Sanction and prosecute gold smugglers and other criminal actors. U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power should work with the U.N. Security Council to designate well-documented conflict gold smugglers in Congo, Uganda, and Burundi for targeted sanctions, as well as urging the International Criminal Court to prosecute illegal gold smugglers. Additionally, the U.S. State Department and U.N. Special Envoy Said Djinnit should pressure Uganda to cut its links to the gold smugglers and tighten airport checks on gold smuggling.