Listen to the podcast (MP3) >>

Read the Activist Brief (PDF) >>

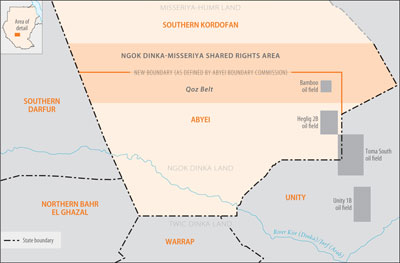

Abyei is the ancestral land of the Ngok Dinka and also hosts the grazing and seasonal migrations of the Misseriya and other nomadic whose livelihoods depend on the area’s rich resources. The 2005 CPA created the Abyei Boundary Commission, which issued a “final and binding” ruling on Abyei’s boundary in July of that year. The NCP rejected the ruling, and a three-year stalemate ensued. The dispute erupted into violence in May 2008, when Sudanese armed forces razed Abyei town and forcibly displaced an estimated 60,000 people—the majority of the town’s population.[2] As is too often the case in Sudan, international diplomats rushed to broker a solution after the damage was done. Following weeks of negotiations, representatives of the NCP and SPLM agreed to refer the boundary dispute to international arbitration (See the Annex for a detailed explanation of this process).The arbitrators’ decision should ultimately determine the final boundary. It is also a real chance for the people of Abyei to finally receive the “peace dividends” promised to them in the CPA in 2005, and to begin consolidating the fragile peace that has been put on hold by the battle over the CPA’s Abyei Protocol.

The history of the Abyei region is complex, but an important theme is its tradition as a “bridge” at the crossroads of Northern and Southern Sudan as well as a critical grazing area to both Misseriya Arabs and Ngok Dinka. The Misseriya and Ngok coexisted in the Abyei area for centuries, with the Misseriya traversing through portions of the Ngok grazing areas during their seasonal migrations as well as a number of other groups, such as the Twich Dinka. The British colonial decision in 1905 to transfer the nine Ngok chiefdoms to Kordofan—allegedly to address slave raiding and place victim and perpetrators under the same provincial administration—has had extended and unintended consequences. The Misseriya and Ngok developed hardened “Northern” and “Southern” identities respectively during Sudan’s North-South civil wars, which in turn raised the stakes for the key questions today: What are Abyei’s boundaries? Who is a “resident”? And, ultimately, is the territory part of the North or the South?

This area—rich in grasslands, forests, swamps, and river systems—also sits atop significant oil reserves which both the Northern and Southern governments seek to control.[3] The ongoing Abyei border dispute will have significant repercussions for long-term wealth-sharing arrangements and the sustainable livelihood of all groups that have traditionally come to depend on its lands and resources. Resolution of the key questions at stake in the Abyei debate will likely continue to plague the Sudanese parties in the remaining months of the CPA interim period, but acceptance of the tribunal’s ruling is a crucial step in getting these discussions on track in order to secure a peaceful and credible 2011 referendum and a stable transition thereafter no matter the outcome.

As Enough noted in a 2008 strategy paper on Abyei, the history of the region in the context of the two North-South civil wars also highlights the Sudanese government’s consistent pattern—across several past regimes—not only of signing agreements with Southern adversaries and then failing to implement them but also of trying to manufacture crises on issues which earlier had been “resolved” at the negotiating table.[4] One example is a referendum promised to the population of Abyei in the 1972 Addis Ababa agreement that ended the first North-South war. Abyei residents were to have voted in a referendum whether to remain in the North or be integrated into the territory of Southern Sudan; this referendum never occurred. The CPA has now guaranteed the residents of Abyei the right to vote in a similar referendum in 2011 at the same time Southern Sudanese will go to the polls to vote in their own referendum. A vote to join southern Sudan in 2011 potentially places Abyei within the borders of an independent South.[5]

Abyei is an issue fraught with intense emotion for the NCP and the SPLM. Ultimate control over coveted oil reserves certainly plays a critical role in this dispute. However, the issue is also linked to the NCP’s repeated promises to Misseriya groups and distinct party constituencies that it would deliver Abyei to the North and secure the permanent inclusion of its lands and resources within a united Arab Sudan. Likewise, many senior SPLM cadres are Ngok Dinka from the region. The Ngok Dinka fought along with the SPLA for their right to see their lands and people rejoined with the South. It is a mistake to view Abyei as merely a fight over oil, as a purely Misseriya-Ngok Dinka conflict, or a project of interest only to Ngok Dinka in the SPLM or the Government of Southern Sudan leadership. The dispute over Abyei is also directly linked to the future of Sudan as a unified or separate state, to the possibility of a stable North-South border in 2011, and to the imperative of a central government in Sudan that does not exploit its peripheral populations. Most importantly, the people of Abyei and its surrounding areas deserve reconciliation and peace—they suffered greatly during Sudan’s civil war and have seen few of the promised “peace dividends.” It is in this context that Abyei’s future is tied so closely to the future of all of Sudan.

During recent discussions in Washington, D.C., the parties reaffirmed their commitment to implement the tribunal’s award and agreed to several key steps: to demarcate the boundaries as per the decision, to disseminate information about the award to local communities, to ensure that the United Nations peacekeeping force in Sudan, or UNMIS, is at full capacity to fulfill its mandate, and to take measures to enhance security, prevent violence, consolidate peace even through the creation of local conflict mitigation processes. But regardless of these recent commitments, the fundamental calculus of the NCP and the SPLM remains the same: Both sides seek to strengthen their positions prior to the 2011 self-determination referendum without forcing the premature collapse of the CPA.[6] The fear, therefore, is that the tribunal’s decision could spark a reaction by one or both of the parties, their proxies, or other spoilers acting with or without the parties’ consent. Any such spark—even if not intended to provoke a return to full-scale civil war—could nonetheless deepen mutual mistrust and increase the possibility of renewed conflict before 2011.

-

UNMIS should immediately increase support for the existing Abyei police and Joint Integrated Units, or JIUs—military units created by the CPA and comprised of both regular Sudanese army and the SPLA—in order to increase their mobility and overall capacity to keep the peace throughout Abyei. UNMIS should also deploy monitors to Sudanese army and SPLA compounds outside of Abyei to reduce the likelihood of minor provocations that could lead to larger outbreaks of violence between these forces.

-

Recent reports indicate that some Sudanese army units that are not legitimately part of the JIUs are currently within the interim Abyei Roadmap boundaries, putting them in clear violation of the agreement. The international community should back UNMIS in urging the parties to recommit to the security provisions of the Abyei Roadmap which are explicit in authorizing only UNMIS forces, the Abyei JIU Battalion and the Abyei Police to be present within Abyei’s interim boundaries. UNMIS should call for the removal of any other forces—local militias, “oil police,” or other armed groups—by the Parties prior to the ruling.

- In anticipation of further instability in Abyei, UNMIS should deploy additional battalions to the region and establish a greater civilian presence on the ground not only through the elections in April 2010, but through the 2011 referenda. Abyei will continue to be a flashpoint, and UNMIS’ presence will be more effective if it establishes longer-term programs and mechanisms to mitigate future violence. UNMIS should consider setting up a demilitarized buffer zone in Abyei to separate the two militaries and mitigate future clashes.[9]

-

Based on its role as a full-time on-the-ground presence in Sudan, UNMIS can signal to the rest of the international community that the tribunal’s ruling should be viewed not just as a flashpoint for war but as a potential chance for peace if the ruling is accepted by the parties and ifthe CPA’s guarantors opt to infuse significantly more programs, personnel, and resources to Abyei in the immediate aftermath of the award. Abyei could become a potential model for development, peace, and reconciliation that could spread along the other North-South border areas, but only if it receives sustained attention and resources from the Sudanese parties, UNMIS, and the rest of the international community.

Conclusion

Why was the Abyei Arbitration Tribunal established and what does it do?

The core question that the PCA’s Abyei Tribunal will answer with its ruling is whether or not the ABC exceeded its mandate to define and demarcate the areas of the Nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms transferred to Kordofan in 1905.If the tribunal finds that there was no excess, the parties’ agreement requires them to the “full and immediate implementation of the ABC report.” If an excess is found, it will proceed to define and delimit the boundaries of the Abyei area based on the submission of the two parties during the arbitration process.

The parties designed the arbitration process and the tribunal’s mandate so that it will result in a decision that determines the final boundaries of the Abyei area. The process also explicitly affirms that the decision will not in any way affect the traditional grazing rights of the Misseriya and other nomads that are already protected and guaranteed by the Abyei Protocol. Regardless of the outcome, these rights are guaranteed. The decision will also not define who is a “resident” of Abyei for purposes of the voter eligibility in the Abyei Referendum of 2011—it will only settle what the boundaries of Abyei are on a map.

While the decision of the Abyei Tribunal is meant to be final and binding, so too were all of the provisions related to CPA’s Abyei Protocol, as well as the original findings of the Abyei Boundaries Commission itself. Without the parties and the international communities’ strongest commitment to guarantee that the arbitral award is implemented, the tribunal’s decision will mean no more than the unimplemented provisions of the protocol and ABC report.

Endnotes