Read the Activist Brief (PDF) >>

Listen to the Podcast (MP3) >>

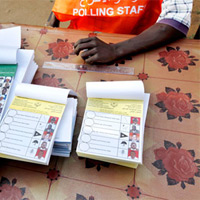

In February 2010, Sudan is scheduled to hold its first democratic elections in 24 years. General elections are required by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, or CPA, which the ruling National Congress Party, or NCP, and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, or SPLM, signed in 2005 to end a second civil conflict between northern and southern Sudan that lasted two decades, killed 2 million people, and displaced 4 million more.

Sudan’s upcoming national election poses a series of thorny questions for the international community, and, to date, these questions have not been acceptably resolved:

-

The NCP is notorious for ignoring the rule of law, persecuting dissenting Sudanese voices, breaking existing agreements, and using ruthless force against civilians. Why should international diplomats believe the NCP will behave any differently during the course of an election, and what guarantees and safeguards will be put in place to prevent cheating?

-

How can a credible election take place in Darfur at a time when the international community is struggling to maintain even bare minimum levels of lifesaving aid there and more than 3 million people are still internally displaced or refugees?

-

How can the national election be credible if a ballot does not take place in Darfur given its significant portion of Sudan’s total population?

-

How do elections fit into a broader strategy of promoting the ultimate goals of power-sharing, governance reform, and the political empowerment of larger numbers of Sudanese citizens?

-

How can the national election be effectively administered given the complexity of the voting systems, the challenge of conducting voter registration during the South’s rainy season, and the slow pace of voter education efforts?

When the CPA was signed over four years ago, credible elections in Sudan were a central element of a multilateral strategy to help the Sudanese people fundamentally alter how their country is governed. It was hoped that credible elections would force Sudan’s ruling party—a group that has waged ruthless war on its citizens for over 20 years—to make a choice: change its behavior and compete at the ballot box or maintain the status quo and be voted from power.

However, four years of selective CPA implementation and declining trust between the NCP and SPLM have badly eroded expectations and fundamentally altered both parties’ political calculations. Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir is now also wanted on war crimes charges for his actions in Darfur. Both the NCP and SPLM view the election with a jaundiced eye. President Bashir and his NCP only see the election as useful if it can be sufficiently manipulated to create some NCP claim to popular legitimacy while keeping threats to the party’s rule weak and divided. The SPLM and many in the South see the election as a distraction from the far more important self-determination referendum in 2011. The challenges of holding a safe and credible election in Africa’s largest and perhaps least- developed country are truly daunting, and the threat of election- related violence—particularly in the South and marginalized areas of the North—is very serious.

Holding timely and safe elections would be a welcome step toward keeping the CPA on track and could provide many communities a much- needed outlet to express popular will. However, given the NCP’s reluctance to embrace free and fair elections that could displace it from power at the national level, elections are unlikely to serve as the main vehicle for radically improving governance and achieving lasting stability in Sudan. Indeed, in light of the numerous delays in key aspects of CPA implementation, the conflict in Darfur, and the international community’s failure to date to harmonize its strategic approach for securing a lasting peace across all of Sudan, the election could prove to be a fiasco.

The United States and other key actors, operating on a tight timeline, need to lower their expectations for the election and develop a multilateral strategy to press the Government of National Unity—the ruling NCP in particular —to enact meaningful reforms regardless of who wins in 2010, revitalize CPA implementation, and establish a framework for talks in Darfur that are consistent with the power-sharing provisions of the CPA. There also has to be a clear and unified international posture with regard to addressing the issue of Darfur, given the near -impossibility of holding a free and fair ballot there.

The international community should use the process of moving forward with the election as an opportunity to press for greater political freedom and participation no matter what the outcome is. The election should be supported as a way for local and regional entities to contest for power, and as an instrument for people to choose their own representatives as a step on the path toward democratic governance—not as a silver bullet that will produce genuine democratic governance.

Deadlines, delays, and decisions

The CPA radically restructured Sudan’s political landscape by creating a multi-tiered power-sharing system of government during a six-year interim period that was supposed to culminate in a 2011 referendum on self-determination for southern Sudan.1

By the end of interim period’s fourth year, the CPA calls for voters to cast ballots in executive and legislative races for the Government of National Unity and state governments, and for southern Sudanese to vote in elections for the semi-autonomous Government of Southern Sudan, or GoSS.2

Election timetable

The CPA aims to end Sudan’s bloodiest conflict as well as address deep-seated economic and political disparities at the center of the state’s many conflicts through its extensive wealth- and power-sharing arrangements. National general elections, it was hoped, would provide a seal of democratic credibility and popular legitimacy to an institutional arrangement that had resulted from bargaining between Sudan’s two most powerful parties rather than balloting among the broader population. A fair vote would ensure that the CPA’s power-sharing structures would evolve from appointed positions to elected offices, with candidates pledging to uphold the CPA. The elections were also seen as a way to broaden the support base by involving groups excluded from the agreement’s negotiations in the broader political process. Ultimately, it was hoped that democratic elections would help make unity attractive to the South by changing the nature of governance in Khartoum and thereby encouraging nationwide political reform.

The CPA divided representation in the new government structures based on proportions agreed to by the NCP and SPLM during negotiations. The National Elections Act? a CPA-mandated law passed by the national assembly last year that provides the rules and guidelines for governing the upcoming elections ?calls for a new proportional allocation scheme.3

Under the current arrangement, members of government are political appointees. Elections would be the first time that the Sudanese people would directly determine who holds these offices. Additionally, state elections in South Kordofan and Blue Nile—two flashpoints along the border between northern and southern Sudan—are designed to initiate “popular consultations,” a vague process in which these states will decide whether to accept, reject, or renegotiate the CPA and its application to their areas.

Both the NCP and SPLM were initially reluctant to hold competitive elections during the interim period, but the international community—particularly the United States—pushed hard to include the elections as a vehicle to entrench and expand peace during CPA negotiations. And while the intentions were admirable, the relative failure of both the signatories and the international community to keep CPA implementation on track now means that the 2010 elections present a myriad of political and operational risks.

On April 1, 2009, Sudan’s National Electoral Commission announced that nationwide executive and legislative elections would occur in February 2010, seven months later than called for by the CPA. Although this was another item on a growing list of missed CPA deadlines, the electoral commission’s decision to delay the historic vote by seven months did not come as a surprise.

Even under a best-case scenario, holding elections on the CPA’s original schedule would have been a tough logistical and operational challenge. Sudan is a massive country, and other than in a relatively small radius around Khartoum, it lacks basic infrastructure and critical services. During the summer months when elections were supposed to occur, intense rains swamp large swathes of the South, rendering remote villages inaccessible and isolated populations stranded. Voter registration and polling are made more difficult by the large number of semi-nomadic pastoralists who migrate with the seasons as well as the lingering effects of displacement caused by decades of conflict. Low literacy rates and little experience with democratic elections compound the problem of voter education for the complicated election process, which in some areas will present voters with as many as 12 ballot papers for races on six different levels. Such a complex procedure—one that would require a sophisticated voter education effort in even the most developed of nations—is a very poor fit for Sudan.

Much of Sudan remains plagued by pervasive insecurity. Clashes in Darfur remain very well and rightly publicized, even as violence has spiked up in numerous localities across southern Sudan. President Bashir’s decision to expel 13 western aid organizations from Darfur, as well as the so-called “Three Areas” of Abyei, Blue Nile, and South Kordofan, has ratcheted up humanitarian and security pressure in exactly those areas where election-related violence is of the greatest concern.4

In the South, the Lord’s Resistance Army, or LRA, unleashed a new wave of attacks and abductions following a botched regional military strike, spearheaded by the Ugandan Army in December 2008, against the rebels’ jungle bases in northeastern Congo.5

In April, hundreds of people were killed in interclan clashes over cattle, access to resources, and local power politics in Jonglei state. These events highlight the combustible mix of weak government structures, stunted development, ineffective security forces, and heavily-armed civilian populations that creates the potential for even greater instability in much of southern Sudan.

The sputtering pace of CPA implementation, elections preparations, and required legal reforms sealed the need for postponing elections. The National Elections Act, which was supposed to be enacted by January 2006, was not passed until July 2008. Five months later—and four months late—President Bashir appointed a committee to lead the National Electoral Commission, which is mandated by the Elections Act to oversee the voting process. The electoral commission formally asked the United Nations for electoral assistance in February, but the broad request led to little actual activity on the ground because the NEC lacked an operational structure beyond its nine-member executive committee and had not set a timetable for the vote. With four months to go and no plan or preparations for a vote, the electoral commission had little choice but to delay the elections. Further, changes proposed by the NCP to laws governing media and security will make free and fair elections even more challenging. Particularly worrisome draft laws currently under parliamentary review would allow Sudan’s security services to detain citizens for 30 days without charge and expand press censorship. Free and fair elections can only plausibly occur in an atmosphere of reduced repression, which has yet to be achieved.

The political calculus of elections

The technical hurdles remain considerable, but the core problems that have hindered elections preparations are political. The premise and promise of elections—democratic transformation, consolidating the peace, and making unity attractive—have been marred by the NCP’s four-year pattern of obstructionism, which has stalled progress on CPA implementation and sapped good will between the parties. The original aspirations of the agreement are no longer is synch with actors’ current agendas, and the tunnel vision of short-term interests and zero-sum calculations has replaced long-term goals of political partnership and national unity.

Both the NCP and SPLM want to use the elections to strengthen their positions prior to the 2011 referendum without precipitating a premature collapse of the CPA or exposing their own internal weaknesses. In many ways the fate of the elections will remain hostage to other CPA implementation issues—including the status of Abyei, border demarcation, referendum preparation, and long-term, wealth-sharing agreements—and whether any progress is made on these matters before February 2010.

The National Congress Party

The NCP is propelled by an instinct for survival and a strategy of opportunism, and its overriding interest is self-preservation. Since the CPA was signed, NCP hardliners have attempted to delay, undermine, or ignore the implementation of any provision that might loosen the party’s grip on power. With two years remaining in the interim period and the growing probability of an independent South, the NCP faces the looming possibility of losing one-third of its territory, many of its oilfields, and control over upstream access to water from the Nile. Continued conflict in Darfur, tense uncertainty in Abyei and South Kordofan, international war crimes charges against the president, and declining oil revenues all risk corroding the NCP’s control beyond Sudan’s riverine core. President Bashir has attempted to hunker down and rally the base after the International Criminal Court’s issuance of an arrest warrant against him for war crimes in Darfur, but the charges have further isolated the NCP internationally and increased internal friction between pragmatists and extremists within the party.

The NCP, under heightened pressure, views elections as both a threat and an opportunity. The party is broadly unpopular and has much to fear from any ballot that genuinely open’s Sudan’s constricted political space. However, the NCP agreed to elections during CPA negotiations in hopes that they could head a political partnership with the SPLM that would draw democratic support and gain international legitimacy while simultaneously subordinating the SPLM’s national ambitions and reducing SPLM presence in power-sharing institutions. As deteriorating confidence in CPA implementation led to dwindling prospects for an electoral partnership, the NCP resorted to its default fallback tactic of obstructionism by neglecting passage of the election law.

The ICC’s arrest warrant against President Bashir altered the NCP’s calculations and once again endowed elections with potential utility as an instrument of legitimacy and control. After the court announced its decision, NCP officials offered the SPLM a deal: if the SPLM agreed to presidential elections in July, the NCP would rapidly push media, security, and other legislation necessary to bringing national laws into conformity with the CPA and enabling fair elections. The SPLM declined, but the NCP’s proposition demonstrates President Bashir’s revived interest in elections as a means to polish his image abroad and purge the party of potential rivals who eye the warrants as an opportunity to push Bashir aside.

The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement

The SPLM has three main interests in the elections. First, the SPLM does not want elections to interfere with the South’s ability to decide its fate through a fair and timely referendum on independence by February 2011. Unimplemented CPA provisions and unrealized peace dividends have reinforced popular perceptions in the South that the NCP is not a reliable peace partner and unity is not a viable option. For many in the South, the CPA’s hopes have been reduced to holding the referendum on schedule and ensuring that the South has an accurately demarcated border and secure access to the oil wealth flowing from the fields that line the region dividing North and South.

Elections potentially cast a shadow over the referendum in several ways. Holding elections in July, during the deluges of the South’s rainy season, would have made it extremely difficult for southerners to vote, for organizations to provide adequate support, and for observers to monitor the fairness of the entire process. Coupled with concerns that the census results—used to determine national power-sharing proportions—dramatically understated the South’s population, some in the SPLM worry that the NCP will use elections to gain a stranglehold in the National Assembly and thwart the referendum. While the SPLM wanted elections during the southern dry season—roughly November to May—to avoid mass disenfranchisement, it also can not allow elections to continue sliding down the same slippery slope of delays that has tripped up CPA implementation. With only two dry seasons remaining before the end of the interim period, the SPLM needed elections to occur during the first dry season to ensure that the second dry season remained reserved for the referendum. Finally, the SPLM does not want the political competition of elections to trigger a military confrontation that could endanger the CPA just when the referendum is within grasp.

The SPLM’s second main interest is to bolster its base in the run-up to the referendum. While smaller political parties in southern Sudan are too weak and fragmented to present a real threat of opposition to the SPLM’s dominant position within GoSS, the SPLM enters the final crucial phase of CPA implementation facing numerous challenges that could be exacerbated by the elections. Southern Sudan is riddled with politicized ethnic divisions among a heavily-armed civilian population that can escalate into destabilizing violence easily exploitable by the NCP. In June 2008, GoSS launched an ineffective civilian disarmament campaign in large part motivated by a desire to neutralize remaining tribal trouble spots prior to elections.

GoSS President and SPLM Chairman Salva Kiir has done an impressive job under difficult circumstances to create a cohesive governing structure that reflects the South’s diversity and responds to its needs, but disappointment with GoSS’s performance remains significant. The GoSS has struggled to deliver a substantial peace dividend to poor, remote regions where access to water, food, health care, economic markets, and education remains elusive for the majority of southerners. The dreadfully slow dispersal of development assistance pledged by Western donors and declining oil revenues have depleted GoSS’s budget, making it more difficult to invest in development, purchase patronage, and pay an army in need of training and modernization. Corruption and the siphoning off of oil funds for personal profit is a serious problem that has bred resentment and disillusionment among desperately impoverished southerners, and understandably chilled enthusiasm among development donors. GoSS’s current push to decentralize will in theory place more power and resources at the disposal of state authorities, increasing the stakes for these seats and potentially accelerating the centrifugal forces. Elections could focus local-level ire at GoSS’s uneven performance, aggravate deep ethnic divisions, and pose a threat to prominent individuals with vested interests in holding onto power.

The SPLM is composed of a mosaic of actors and a variety of interests that reflects the South’s complexity. The SPLM has historically struggled to reconcile its own competing visions for Sudan, the “South-first” strategy of secession and John Garang’s “New Sudan” strategy of national unity through democratic transformation. Salva Kiir has worked to ensure that both factions are represented within GoSS, but the vying visions have not been reconciled and will likely come into sharper focus as the referendum approaches. Some spoilers who fought against the SPLA during the war and joined GoSS for the spoils may be biding their time until they have an interest and opportunity to bolt. For the SPLM, elections, and the rapidly approaching referendum run the risk of exposing these rifts and hastening a reckoning or realignment of interests within the party.

Finally, the SPLM’s third main interest—at least among the South-first bloc—is to develop the building blocks of a new state that will have internal stability and international support. The GoSS government elected in February 2010 will be responsible for steering the South during the referendum period and beyond. The vast majority in the South seems eager to vote for independence were the referendum held today, while a fledgling state in southern Sudan will face immense economic, political, and security challenges: poor but endowed with the mixed blessing of oil, sprawling but landlocked and bordering numerous security vacuums, and uneasily united in opposition toward NCP misrule but divided by internal schisms. Establishing democratically elected institutions will strengthen the South’s standing as well as claims for recognition and assistance among the international community.

Thus far, the SPLM’s strategy toward elections reflects the diversity of its multiple, moving parts. Publicly, many SPLM officials claim that the party will use the general elections to mobilize the marginalized masses across Sudan, unseat President Bashir, and replace the NCP’s majority in the National Assembly with a coalition of the periphery led by the SPLM. This, they argue, is not only consistent with Garang’s vision, but is also supported by secessionists who think that the only way to ensure the referendum is to gain control of the National Assembly. While the threat of reaching out to northern constituencies and expanding the SPLM’s existing presence in the north may have utility as a bargaining chip with the NCP to build leverage and gain concessions in other contentious CPA areas, this is unlikely to become reality. Pushing for the presidency or attempting to capture Khartoum by the ballot would be a high-risk strategy that could provoke a showdown with the NCP—remains in a strong position in relation to northern opposition parties —while bringing little benefit for the majority of southerners who would prefer to exit rather than fix Sudan.

The SPLM will also need to decide which candidate to run against President Bashir. GoSS President Kiir, who is also vice president the GNU, cannot run for both the presidency of GoSS and GNU. For those loyal to Garang’s approach, elections may be the last chance to argue that a unified Sudan serves the South’s interests. If the NCP stifles elections and further marginalizes the South, then the staunchest advocates of the New Sudan strategy may reach the point where they no longer see the practicality of any path other than independence.

What about elections in Darfur?

The ongoing catastrophe in Darfur poses one of the greatest challenges to national elections. The volatile security environment and contested census results (most accounts suggest that the census in Darfur was even less comprehensive and representative than in the South) cast serious doubt as to whether elections can even be held. And National elections can hardly be considered credible if 7 million people—more than 17 percent of Sudan’s estimated population of 41 million—are disenfranchised. If the decision is taken to hold elections in Darfur, the obstacles are overwhelming. Aside from resolving disputes over the census and logistical and security hurdles, overcoming pervasive distrust of the government poses a serious challenge. For example, many displaced Darfuris are deeply concerned that registering as residents of internally displaced persons’ camps will delegitimize their land rights outside these camps. In this charged atmosphere, elections could actually lead to more violence and, potentially, give the government an excuse to forcibly close displaced persons camps. The international community, which remains eager—at least rhetorically—for elections to stay on track, has not made clear their position on how the issue of Darfur and the elections should be addressed, and this gap remains a yawning one.

Rewards and risks

Democratic elections are still vital to the fate of the CPA and the future of Sudan, but it will take more than a poorly managed election to address the root of Sudan’s crisis—the hoarding of wealth and power in Khartoum at the expense of a marginalized periphery. It is important, then, to manage expectations and have realistic goals that reflect the current challenges and constraints. Elections will not magically transform Sudan, but pushing to complete elections peacefully in February 2010 could provide impetus to clear the cluttered backlog of delayed CPA benchmarks and help identify the major challenges to holding a credible referendum in 2011.

Postponing the vote until February was a first step to adequately prepare and support the electoral process, but major risks and concerns remain. The new election timetable announced by the electoral commission leaves many problems unanswered and raises many new questions. On May 23, the electoral commission announced plans to establish state committees throughout the country. Six days later, it signed an agreement with UNDP that paves the way for $68.7 million in electoral assistance. However, the electoral commission does not yet have operational structure in place, and it will take months at best for it to establish regional offices, hire and deploy staff, and begin functioning effectively on the ground. If the electoral commission doesn’t build basic capacity by the beginning of June, according to some observers in Juba, it is unlikely that they will be able to hold and manage elections—credible or not—during the next dry season.

The electoral commission’s decision to conduct voter registration during the South’s rainy season is also potentially problematic. Just as there were concerns that polling during the rainy season would lead to disenfranchisement, attempting to register during the same period could lead to large numbers being left off the voting rolls in the South. Lastly, citizens will not be able to campaign and participate in the electoral process without fear of censorship, repression, and human rights abuses, unless the National Assembly amends and alters existing legislation—including the press and security laws—to provide adequate safeguards for civil liberties.

The very challenging security environment in which these elections must be held is equally daunting. Absent swift implementation of a political settlement in Darfur—something that looks exceedingly unlikely absent much stronger U.S. leadership—elections can simply not be held in that region of the country, which is home to approximately 7 million people. In other marginalized areas—particularly in the South—the potential for ethnic manipulation and violence is high. Elections will bring political competition and confrontation within heavily militarized and mutually suspicious populations and give the NCP an opportunity to stoke intercommunal violence. Small sparks on a local level from tribal power politics or local grievances can spiral out of control rapidly and state security forces have little capacity to provide security or contain conflict. And if large numbers of people are disenfranchised by logistical complications or political manipulations, electoral losers may become peace spoilers.

Finally, the GoSS has rejected the recently released results of Sudan’s national population census, which is supposed to be used by the electoral commission to delineate constituencies for the elections. According to the census results, the South comprises 21 percent of Sudan’ total population and only 520,000 southerners live in the North. Comparatively, under the CPA’s pre-election power-sharing proportions, the South is currently allocated 34 percent of seats in the National Assembly, and GoSS officials had previously declared that they would reject the census and could boycott elections if the results did not give the South 30 percent of the population. The continued impasse over the census results could derail not only the elections preparations but the entire CPA.

How to address elections

The landscape in Sudan has changed in the four years since the CPA was signed, and the international community has to adjust its expectations for the elections and recalibrate its strategy to revive CPA implementation. In many ways, the slow pace of CPA implementation to date, and the likelihood of a badly flawed election mean that the international community will enmesh itself in a very difficult game of damage control and limitation.

Elections are a litmus test for international engagement more generally, which must be more consistent, coordinated, and resolute to prevent Sudan from plunging back into war. All involved must remember that elections are one element of a much larger peace process—not the other way around. The goal of international support should be an overarching peace for all of Sudan accompanied by a peaceful vote that helps create creating momentum and builds confidence for implementing the remaining major CPA provisions, particularly how to hold a credible self-determination referendum. The United States plans to spend $95 million to support the elections—its third largest commitment to electoral support behind Iraq and Afghanistan—and the United Nations and other donors are also prepared to provide substantial financial and technical assistance. This eagerness to support elections is not surprising, but donors must be wary about stamping a seal of approval on a process that could embolden President Bashir as he faces war crimes charges and continues to practice divide and rule tactics in Darfur and the South. The international community should make clear that it will not unconditionally support elections that do not meet baseline standards such as a level playing field for political parties to compete and an opportunity for all entitled individuals to freely exercise their right to vote.

The main priorities for the international community must the following:

1. Building capacity

- Ensure that the electoral commission has an operational structure in place as soon as possible: While it now has a framework and funding, the electoral commission still lacks the necessary field infrastructure and capacity—including functional offices, trained staff, and physical supplies—necessary to adequately prepare and conduct elections during the next dry season. The pace of the electoral commission’s development has been slowed by a lack of political will in Khartoum, and the commission’s leadership must be open and its decision-making transparent to build confidence in the electoral process.

-

Educate voters: The elections process as determined by the CPA is extraordinarily complicated and many Sudanese have never voted before. In southern Sudan, for example, voters will be asked to complete twelve separate ballots. Low literacy rates—only 24 percent in the South—add to the challenges of ensuring that voters understand how the election will work. Donors should support basic voter education programs so that Sudanese can participate meaningfully in the election, and have a greater understanding of their fundamental rights even if the election does not come to pass.

2. Mitigating violence

- Bolster the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Southern Sudan, or UNMIS: In an ethnically charged environment, national elections have the potential to further destabilize parts of the country and could be the spark for further conflict. At this late point, the safety of the elections must take priority, and UNMIS should be bolstered from the pre-election period to prevent and resolve emerging conflicts that will arise or be stoked in the context of the electoral process. The ability to get U.N. personnel on the ground in real time—even in remote locations—to monitor and report after local clashes will be essential to preventing small incidents from blowing up into large ones.

-

Postpone elections in Darfur:6

Holding elections in Darfur without an inclusive political settlement will not contribute to peace in the region and could make things worse. A more autonomous regional government and new arrangements for wealth and power sharing are core demands of most Darfuris. Thus, a majority of Darfuris would reject not only any outcome that legitimizes the current political leadership in Darfur, which is drawn almost exclusively from the NCP, but also the very structure of governance in the region. The priority for Darfur right now must be the negotiation of a peace agreement that meets the core demands of Darfuris for representative wealth and power sharing and allows displaced persons to return home voluntarily and safely. Elections should only be held once that fundamental goal has been achieved.

- Target election support to the Three Areas: The Three Areas have not received a meaningful peace dividend from the CPA. In South Kordofan and Blue Nile, where there is little understanding of the CPA, high levels of militarization, and no option for a referendum as an exit strategy should the NCP continue to quash meaningful political participation by the nation’s periphery. In Abyei, which will vote in 2011 whether to stay with the North or become part of the South, the elections are seen as a dry run for the referendum. Working toward more credible results in the Three Areas is thus critical.

- Support conflict prevention and management programs: Recent clashes in Malakal and Jonglei demonstrate the potential for destabilizing bloodshed and the need to expand support for local-level conflict resolution initiatives that identity flashpoints and encourage community participation in peace-building activities to prevent violence during the elections.

3. Focusing on the big picture

- Press for comprehensive governance reform: The process of moving forward with the legal framework for elections should be used as an opportunity to revise existing national laws, such as those governing the press, that make both fair elections and more accountable government extraordinarily difficult. In the South, the international community has an important opportunity to stress that continued (and vital) assistance is dependent on practical steps by the GoSS to combat corruption and establish sensible plans for tackling key development challenges that reflect community input.

-

Initiate a diplomatic push for progress on the remaining major CPA challenges and end the war in Darfur: Support for elections must be part of a sustained international strategy of incentives, disincentives, and leverage that will help prevent Sudan from relapsing into a third North-South war, allow the South to hold a credible self-determination referendum in 2011, and help achieve a political settlement to end the war in Darfur and allow refugees and internally displaced persons to return home.7

END NOTES

1. Abyei, an oil-rich and ethnically-charged area along the contested north/south border, will also hold a referendum on whether to be part of northern or southern Sudan. For a background on Abyei, see “Abyei, Sudan’s ‘Kashmir’,” by Roger Winter and John Prendergast, available here. return

2. The Government of National Unity has a bicameral legislature composed of the Council of States, which has 2 representatives from each of Sudan’s 25 states, and the National Assembly.return

3. Under the CPA, the president of the unity government is from the NCP and the First Vice President is from the SPLM, while in the National Assembly, the NCP has 52 percent of the seats, the SPLM 28 percent, other northern political forces 14 percent, and other southern political forces 6 percent. In contrast, in the post-election National Assembly, 60 percent will be elected to represent geographical constituencies, 25 percent will be women elected by proportional representation from party lists, and 15 percent will be political parties elected by proportional representation from party lists. return

4. The disputed border between northern and southern Sudan, lined with oilfields essential to the both areas budgets, is tense. Clashes in February between the SPLA and Sudanese army in Malakal, which killed 60 soldiers and civilians, demonstrate how quickly the situation can flare out of control. return

5. According to estimates by the U.N. Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the beginning of April, LRA-related incidents in the southern Sudan states of Western and Central Equatorial have displaced 37,000, killed 160, and lead to the abduction of 83 children and adults. As a result of LRA attacks in Congo, 17,695 refugees have spilled over the border into Sudan. For Enough’s recommendations on how to end the threat posed by the LRA see “Finishing the Fight Against the LRA”, by Julia Spiegel and Noel Atama, available here. return

6. There is a precedent for postponing elections for a region of Sudan in times of war. National elections in 1965 were not held in parts of southern Sudan (especially Equatoria) because of lack of security. By-elections were held in the south 1967 to complete the parliament. Even then, however, the results were largely unrepresentative of southerners’ political views, as the voters were mainly northerners living in the south. For a history of elections in Sudan, see “Elections in Sudan: Learning from Experience”, available here.return

7. For Enough’s comprehensive strategy for peace in Sudan see “President Obama and Sudan: A blueprint for Peace”, available here. return