By Nathalia Dukhan

Executive Summary

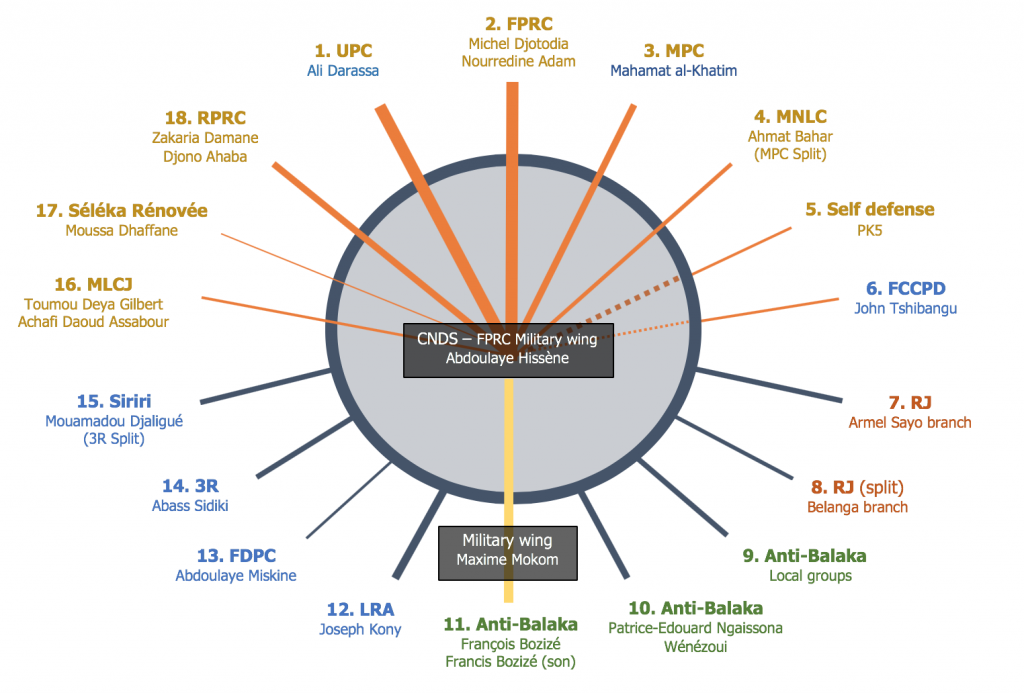

Five years after war broke out in the Central African Republic (CAR), the conflict has no end in sight.[i] The country has become ungovernable over time and is sinking into a structural crisis. Despite being branded a low-intensity conflict, it is brutal and bloody. Entire communities are regularly targeted in carefully orchestrated military operations. Politico-military groups and various armed factions that effectively rule the country are held responsible for the chaos.[ii] Since 2014, the proliferation of these armed groups across the country[iii] has confirmed how deeply rooted politico-criminal entrepreneurship has become. In fact, it is now a booming business sector. In rural areas, these groups are the main source of employment for disillusioned youths. They also offer outlets for violent mercenaries from neighboring countries, especially Chad and Sudan.[iv] The proliferation of these groups, along with the transnational trafficking of weapons and natural resources, presents high stakes for the entire Central African region.

Labeled as a civil war, the CAR conflict presents at first glance all the symptoms of a war between ethnic and religious communities. While armed groups obtain ever-more sophisticated military equipment and mobilize increasingly well-trained forces,[v] local communities also arm themselves and sometimes take part in combat. As United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres indicated in a recent report, insecurity is on the rise. “The security situation in Bangui and other parts of the country has deteriorated since April 2018, amid a resurgence of sectarian rhetoric and intercommunal strife, which has undermined popular trust in the State and in the national defense and security forces,” he wrote.[vi] Between April and May 2018, the United Nations stabilization mission in CAR (MINUSCA) counted 39 articles published in 11 national newspapers inciting discrimination and violence.[vii] This is hardly a new phenomenon. Since 2005, several ethnic and religious communities have faced targeted discrimination and assassinations (see annex).[viii] In 2018, Christians also became targets, in addition to repeated attacks on Muslims.[ix]In addition to their predatory ambitions, several armed group leaders readily display their thirst for power, which forms the basis of their often short-lived, opportunistic alliances. While these warlords are applauded when they “reconcile,” their guns don’t fall silent. Military tactics simply change to bring about new centers of power. These shifting tactics conceal an accumulation of national and foreign actors’ hidden, sometimes contradictory agendas. When the stakes change, so do alliances, and the war takes a new turn. These hidden agendas are often unknown to the greater public but are nonetheless at the heart of instability in CAR.

Brandished as a weapon of war, sectarian violence aims to divide and incite hatred between communities. In the absence of the rule of law, those targeted seek protection from the same actors fueling the rising tensions. Those “protectors” are in fact seeking a popular base for legitimacy. They exploit a sense of ethnic or religious solidarity in order to enlist young fighters and mobilize funding. In this toxic atmosphere, alliances between armed groups proliferate and grow stronger. The more perpetrators of mass atrocities represent a threat, the more their negotiating power increases and the more they gain. The leader of the FPRC/CNDS armed group, Abdoulaye Hissène, clearly illustrates this system when he declares: “Men must die, and blood must be shed for people (like me) to get rich.”[x]

Considered legitimate political interlocutors with whom peace has to be negotiated, despite being recognized as criminals, armed group leaders exact a high price for their positions of power. Meanwhile, mediation winds its way slowly in CAR, although no sustainable or coherent solution has emerged. In fact, various actors use these political “dialogues” to gain influence. The arms race continues unabated, pursued by both armed groups and the government,[xi] assisted in the task by networks of foreign actors in a climate of impunity. This situation is prompting fears of escalating violence bloodier than ever before.

Following a May 2018 attack on the Church of Fatima in the capital, Bangui,[xii] the Platform of Religious Confessions (PCRC) criticized in a memorandum “the aims of certain neighboring and foreign countries seeking to impose hidden agendas in CAR in order to occupy it, through armed groups that are guided and maintained by them.”[xiii] The worst conspiracy theories gain traction in CAR, where the president’s team exhibits paranoid fears of a coup. Rumors persist of plots to remove President Faustin-Archange Touadéra from office before the next elections in 2021. In a country that has experienced five successful coups since 1960 – and numerous attempts foiled by allied countries – the threat is taken seriously.

The president has made few allies during his two years in power. Most of the political class in CAR and heads of state in the Central African sub-region share a negative view of his term. France sees him as a threat to its interests in this former colony. Fixated on remaining in power, the presidential clan is focusing on military and economic cooperation with the Sudan – Russia – China axis. Meanwhile, France is making diplomatic efforts and using stratagems to maintain its influence in Africa, under the watchful eye of the United States. Until recently, the CAR conflict had been termed a civil war, but it is now beginning to share characteristics with the war in Syria, thanks to its internationalization.