Download the full report.

Download the full report.

Résumé analytique et recommandations

Résumé analytique et recommandations

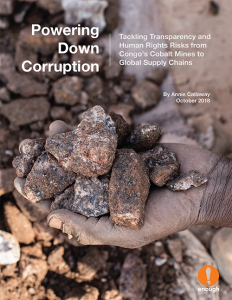

By Annie Callaway

Executive Summary

The copper and cobalt industry in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo) has become “a cash cow for those in power in Kinshasa and their acolytes here in the [Lualaba] province,” a miner at a cooperative in Kolwezi city told the Enough Project in February, 2018. “It’s millions and millions of dollars that they have been reaping to fill their pockets for years.”[i] A Congolese representative from a nongovernmental organization focused on natural resource transparency further warned: “The increase in international demand for cobalt is likely to trigger a cobalt rush with more militarization of the mines and more human rights violations. … The political and security landscape being volatile in Congo, advocacy organizations and [companies] can choose to be preemptive now or wait [to take action] until the situation gets out of control.”[ii]

These observations encapsulate the precipice on which Congo’s cobalt industry rests: continue to be consumed by corrupt or violent actors—as has historically been the case for much of the country’s natural resource wealth, including cobalt—or emerge as an example that breaks the exploitation cycle and uses the mounting international market rush as an opportunity to build a responsible, transparent, and stable cobalt sector. As it stands today, cobalt benefits and motivates some of the largest corruption networks in Congo, and is an important source of finance for President Joseph Kabila’s regime.[iii] The wide spectrum of corruption in the cobalt trade combined with abuses at and around cobalt mine sites and links to state-sanctioned violence and grand corruption forms a crucial pillar in Congo’s violent kleptocratic system. It is therefore essential to tackle the underlying issues of corruption and opaque business dealings in order to support correlating goals of peace, human rights, and good governance.

Congo produced and estimated 58 percent of the world’s cobalt in 2017.[iv] With demand increasing and electric vehicle manufacturers and consumer electronics companies scrambling to secure their access to this critical material, there is a nearly unprecedented opportunity for companies to engage proactively and continuously in dedicated supply chain due diligence—or for corrupt networks to make millions in a climate of scarce regulation and oversight.

Cobalt is mined on both large-scale and artisanal concessions in Congo, each presenting its own set of challenges. Industrial or large-scale mining (LSM) lacks transparency in several key areas of contracting, subcontracting, and joint venture disclosure practices. Artisanal or small-scale mining (ASM) in some cobalt mining areas has links to illegal and corrupt involvement of armed military actors, nontransparent documentation of production and export data, and human rights abuses such as child labor and hazardous working conditions. Connections back to President Kabila and his regime emerge in both artisanal and industrial mining.[v]

If managed transparently and responsibly, cobalt revenues could help alleviate poverty in Congo and be a backbone for development. Especially as Congo implements a new mining code that considerably raises royalties on cobalt, a responsible and transparent trade could, in theory, have nearly unprecedented social and development benefits. To complement these, companies using cobalt to propel forward renewable energy technologies such as electric vehicles and rechargeable batteries could also share the benefits of these technologies with Congo’s mining communities.

Hundreds of millions of dollars went missing from Congo’s state-owned mining company, Gécamines, between 2011 and 2014,[vi] with direct ties from this missing money to deals with international copper and cobalt mining companies. The networks of corruption extend beyond Congo’s borders to foreign commercial facilitators such as key Kabila financier Dan Gertler, whom the U.S. government sanctioned in 2017 for generating illicit wealth, mainly from corrupt and opaque mining deals in Congo.[vii] And several industrial cobalt and copper mining companies operating in Congo are currently under investigation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada for their potential role in corrupt activities.[viii]

The scale of potential revenue in this trade dwarfs that of tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold—otherwise known collectively as conflict minerals. Although cobalt mines are not located in areas with a history of armed conflict, as was the case with conflict minerals in Congo’s Kivu provinces, the cobalt industry is nonetheless connected to violence. The Republican Guard—the president’s elite security force—has been documented illegally controlling artisanal mine sites, sometimes through use of violence or threat thereof. These abuses are in addition to the documented accounts of child labor,[ix] sexual exploitation,[x] and other violations of human rights.

In order to ensure that human rights abuses are not used as a means to an end for corrupt actors looking to access massive profit illicitly, companies must actively incorporate transparency initiatives into their sourcing protocols. Automotive, consumer electronics, and other end-user companies that drive global demand for cobalt have an important opportunity to implement and help enforce transparency and anticorruption measures in order to ensure that their supply chains are responsible and that Congolese citizens are able to benefit from their country’s natural resources. Building on existing frameworks developed to address child labor and other related issues in Congo’s artisanal cobalt sector, companies should take the opportunity to also establish rigorous processes to enhance contract and ownership transparency and illuminate the opaque linkages to grand corruption and human rights abuses in the global cobalt supply chain, conduct due diligence to mitigate the risks associated with corruption, and create a new standard operating environment in which corruption and human rights abuses are not a part of business.

Want to learn more and take action? Visit our cobalt campaign page at enoughproject.org/cobalt