Machetes and bullets near the border in Gisenyi, Rwanda. July 26, 1994. UN Photo/John Isaac.

Twenty-five years ago, on the night of April 6, 1994, a plane carrying the then president of Rwanda, Juvénal Habyarimana, and the President of Burundi, Cyprien Ntaryamira, was shot down, killing everyone on board. Within an hour of the plane crash, the Presidential Guard, together with members of the Rwandan armed forces (FAR) and Hutu militia groups, set up roadblocks and barricades and began slaughtering Tutsis and moderate Hutus. The mass killings in Kigali quickly spread to the rest of Rwanda. During this period, local officials and government-sponsored radio stations called on ordinary Rwandan civilians to murder their Tutsi neighbors.

The international media reported live on the killings from Rwanda. The world watched the genocide from the beginning up until the very end. The genocide took place in full view of the international community

The United Nations had forces on the ground in Rwanda, but the UN peacekeeping mission was given orders not to intervene. One year after the American peacekeeping forces were killed in Somalia, the US was hesitant to get involved in another conflict in the region. In fact, the US, the Belgian government, and the entire UN Security Council voted to withdraw 90% of peacekeepers in Rwanda, leaving the Tutsi minority and other vulnerable populations to face the genocide on their own.

In just 100 days, from April 7 to mid-July 1994, the genocide took more than 800,000 lives, the fastest rate of mass murder in recorded history.

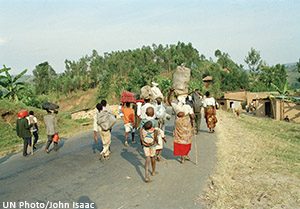

Rwandan refugees returning from Goma on a road near Gisenyi, Rwanda. July 26, 1994. UN Photo/John Isaac.

The book Congo Stories, by Enough’s Founding Director John Prendergast and Congolese Activist Fidel Bafilemba, explains: “The aftermath of the Rwandan genocide spilled over into Congo in the mid-1990s, acting like gasoline on the fire of the preexisting intercommunal tensions and conflict. The situation was made worse by the rapacious divide-and-conquer strategy of the Congolese government in its eastern provinces bordering Rwanda. The Rwandan Hutu soldiers and militias hiding in Congolese refugee camps resumed their attacks on Rwandans from across the border, continuing the Rwandan civil war on Congolese soil. They maintained their genocidal ideology aimed at destroying the Tutsi. Congolese president Mobutu began to provide support to some of the Rwandan Hutu insurgents in the camps.”

The legacy of the genocide in Rwanda extends beyond its borders and reminds us of the importance of understanding history. What would have happened if American peacekeeping forces had not been dragged through the streets of Mogadishu one year before? What would have happened If the UN peacekeeping forces never left Rwanda? What would the trajectory of Congo look like if Rwandan Hutu militias were not hiding in Congo? What would the international response have been if more people learned and understood the history of the region and its people?

Teaching and learning about genocide allows future generations to learn from humanity’s mistakes; to learn the importance of protecting and understanding not just their individual human rights but also the universal one we share.

In Congo Stories, Prendergast and Bafilemba write: “First, there is the critical lesson we all learn in school that we need to understand the mistakes of history in order to not repeat them. Beyond that, there is simply no way to begin healing unless historical wounds are acknowledged and addressed. We need to better understand and more honestly acknowledge the truth behind our shared history. We must understand abusive and unjust historical patterns in order to break them. To build a better future, we should seek to fully understand the “structural sins” of the past. Finally, acting on a true understanding of history will allow us to liberate ourselves from centuries of bigotry and exploitation”

Members of the Security Council vote on a resolution concerning Rwanda. June 8, 1994. UN Photo.

Teaching about genocide and mass atrocities is never easy. Teaching numbers is important, but storytelling and personal narratives are irreplaceable tools when educating young people about genocide and how to prevent it from ever happening again.

The Rwandan genocide was not just the extinguishing of 800,000 lives; it was the murder of one person at a time. Every single one had a story, a dream, and a life that was taken away from them, and every survivor has a story to tell that would teach about overcoming, and the amazing human resilience to stand up and fight again, a fight for freedom, understanding, and human rights.

In a memoir published in the Guardian, Jean Louis Mazimpaka, a survivor of the Rwandan genocide, said “ It’s hard for survivors to speak about what happened but it helps me, because I am doing something to continue the memory of what happened. People are shocked that it happened, that they didn’t know. It is exhausting, but that is what we have left, the story of our loved ones.”

If we are to prevent future genocide and mass atrocities, the whole world must educate young people about it. We owe it to those who lost their lives, to survivors, and to future generations. Let’s teach their stories!

——

The “Congo Stories” book has a free study guide designed to be integrated into curriculum to accompany the text designed for classrooms and other educational settings.

The Enough Project’s Portal is the online resource center for activists, students, and educators. It includes Enough Project’s Library, which features books and films along with resources for educators including curriculum guides.