GOMA, Democratic Republic of Congo — President Kabila’s successful effort to revise the electoral law in the Congolese constitution last week sparked controversy, prompting opposition and human rights groups to warn that the changes are a threat to national unity. Kabila’s controversial move marks the start of what is likely to be a tumultuous period leading up to the vote in November 2011 and underscores the need for international attention and involvement.

Congo’s constitution is the product of peace talks in Sun City, South Africa in 2002 and a constitutional review process underway since in 2006. Referencing the Sun City talks, Vital Kamerhe, former Congolese National Assembly president and now president of the opposition party the Union for the Congolese Nation, said, “We were in war and we battled hard with the help of regional leaders and the international community, and we were able to reconcile. Only four years after the first mandate, one can’t just decide the constitution review without taking the risk of compromising the national unity.”

The constitutional changes enacted by Kabila eliminate the multi-round run-off vote system used during the 2006 elections. Under the new procedure, the candidate with the largest percentage of votes – even if that proportion is less than 50 percent – would win the seat.

Cardinal Laurent Mosengo Pasinnya, president of the Episcopal Conference of Congo, spoke for many when he voiced disapproval of President Kabila’s proposal. Cardinal Pasinnya noted that a president elected with only 20 percent of the votes would not be at all representative of all Congolese people. Human rights group Voice of the Voiceless highlighted the potentially destabilizing nature of a process that fails to rally all ethnic strata if a president is elected after just one round of voting.

Congolese Information Minister Lambert Mende Omalanga sought to justify Kabila’s decision. “We experimented in the 2006 presidential election by direct votes in two rounds, and we found that it is not in the interests of our people in terms of economic, political, and security viewpoints,” Mende said. “Economically, it is obvious that the best interests of the Congolese people lies in the pattern of an electoral system that is the least expensive. We are a poor country, a country in debt, a country under reconstruction, and a country that is fragile, we need to share the meager resources we have among all the people’s needs,” he said.

This year’s elections are estimated to cost roughly $700 million in contrast to those of 2006, which cost $500 million and were funded with over 90 percent contribution from the international community. Thus far, the international community has only donated $90 million to the 2011 process. Joseph Kabila said the Congolese people would be able to save $350 million through a one round presidential election, as the government struggles to raise international contributions.

But opposition leader Vital Kamerhe accused the president and his cabinet of using the cost of the election as an excuse. “There is a hidden agenda,” he said. “As far as we are concerned, respect for the constitution, the national consensus, and national cohesion are paramount because we do not want to set the stage for Congo balkanization.”

Opposition groups in Parliament push back

Kabila’s proposed changes didn’t easily sail through Parliament either. In a plenary session at Congo’s lower house on January 11, the adoption of the constitution review unfolded against a backdrop of chaos. Parliamentarians blew whistles, hurled insults, and ultimately threw punches on the Parliament floor.

In an attempt to block the passage of Kabila’s revisions, François Mwamba and other opposition members invaded the rostrum. Whistles in their mouths, they wreaked havoc and several times attempted to call out the Parliament president, Evariste Boshab, who was compelled to withdraw to his office because of the mounting hostility. Vitriolic reactions and accusations from one side to another over the Parliament microphone continued throughout the day.

Over 200 opposition members ultimately walked out of the session in protest of the day’s proceedings, calling on the Congolese people to witness the hostile takeover of the president’s power in Kinshasa. Once outside, the opposition’s parliamentary spokesperson said on behalf of the group: "The opposition judged it urgent to leave the session because the bureau has infringed the rules, the constitution, and it doesn’t respect the procedure. We filed this morning a motion of no confidence against President Evariste Boshab. The Congolese people must take note of what happening," he said. Despite the resistance, Kabila’s changes were approved.

Follow-up from Secretary Clinton?

Given its emphasis on the need for democracy and good governance, the international community has no excuse for watching passively what is looming on the horizon in Congo. This year’s elections have the potential to destabilize not only Congo but also the wider region.

There is good reason for the American administration to be focusing on the referendum in South Sudan for now. But over a year after visiting the region and victims in the east, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton must follow up on her commitment, personally and on behalf of the U.S. government, to prioritize efforts to mitigate and prevent conflict.

The international community can grow weary of throwing millions of dollars towards helping the Congo, but supporting a democratic process does not need financial assistance alone. It is also diplomatic and political; what is needed is a genuine commitment resulting in an active and clear foreign policy toward the Congo.

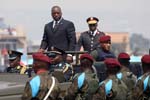

Photo: President Kabila in a parade (AP)