If you have been reading about eastern Congo lately, one name has been stealing headlines: M23. In a dramatic show of force, the Rwanda-supported rebel militia group led by ICC indictee Bosco Ntaganda took control of strategically important Goma in mid- November and then earned a place at the ongoing peace talks in Kampala by ending their 11-day occupation earlier this week.

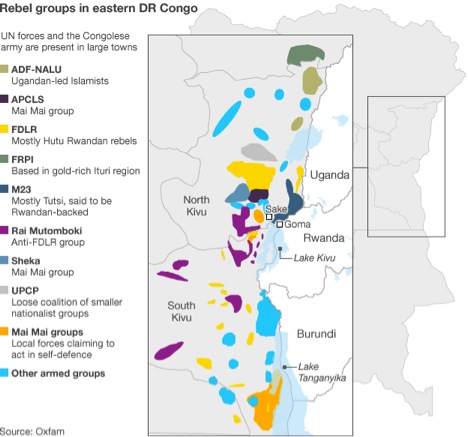

However, focusing on the M23 belies the complexity of the highly militarized politics of eastern Congo. Currently, a kaleidoscope of armed groups control swathes of territory across the Kivus. According to a new report from Oxfam, over 25 armed militia groups operating in eastern Congo have made communities in the region the latest “commodities of war.”

Drawing on hundreds of interviews and focus group discussions with affected populations across the Kivus, Oxfam concludes that “government soldiers, armed rebels, police, and civilian authorities are all vying for the right to exploit local communities and extort money or goods from them, pushing people further into poverty and undermining their efforts to earn a living.”

Since many areas frequently change hands between state and militia control, respondents complained of paying bribes and fees to both sets of armed actors to ensure their protection and continued access to their fields. The report quotes a woman from Fizi explaining, “when [government] troops arrive, there is a complete change in the area. People are taxed for having collaborated with elements of the armed groups.” However, later when rebels regain control over a community, “they take revenge on the local population, saying they spy for the FARDC and pass them information.”

As alliances shift and various factions jockey for control over territory and strategic trade routes, the situation has grown ripe for manipulation by external actors. Now more than ever, a holistic and inclusive peace process is critical. The recent proliferation of armed groups across the region undermines the security of the civilian population, exacerbates simmering ethnic tensions, and continues to destabilize the mineral-rich area.

The root causes and underlying dynamics driving instability in eastern Congo will never be resolved by closed door, back room negotiations among the biggest guns. As Aaron Hall and John Prendergast argue in their recent policy brief, a “broadened” peace process is critical to resolving these fundamental issues. The emergence of the M23 underscores the fundamental flaws with the 2009 peace deal between the government and the most prominent rebel group at that time, the National Congress for the Defense of the People, or CNDP. Without a credible high-level, internationally backed mediator to shepherd talks, the well-worn pattern of recurring crises in eastern Congo cannot be broken.