Listen to the Podcast (MP3) >>

Crucial deadlines are nearing in the interim period of Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement, or CPA, which ended a 22-year civil war between the North and the South. And as the deadlines grow closer the international community is at risk of sleepwalking toward the coming 2010 elections and the following southern referendum without mustering the necessary energy to stop the looming threat of war. The Obama administration is to be congratulated for bringing together key signatories and more than 30 countries and organizations in Washington this week in an effort to reinvigorate CPA implementation, but much more will need to be done. Recent events in southern Sudan highlight the many problems with the current approach to the complex and ambitious project of implementing the agreement. Increasingly hostile relations between the National Congress Party, or NCP, and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, or SPLM; a recent spate of intercommunal violence throughout the South; and an array of abandoned or unimplemented CPA provisions threaten to derail the CPA before 2011, when the semiautonomous South will likely vote for its independence from Sudan, marking the end of what is commonly referred to as the interim period. Perhaps most importantly, parties to the CPA, particularly the NCP, have not faced any cost from the international community for a failure to implement key provisions of the agreement. Until the international community changes this fundamental dynamic, no conferences or consultations will change the basic facts on the ground.

With less than 19 months remaining before the end of the CPA interim period, the international community can no longer afford to half-heartedly address these worrisome dynamics. Renewed Sudanese civil war could bring wholesale violence on a terrible scale while further destabilizing the entire region. A renewed diplomatic push in the waning period of CPA implementation built around the use of principled and direct penalties and incentives could prevent Sudan from relapsing—but this strategy will have to be more sustained, coordinated, and strategic than prior efforts, which have failed to adequately respond to recent challenges and opportunities. If there continues to be no cost for flouting key provisions of the agreement, renewed conflict is likely.

The rough road to 2011: Challenges and dangers

When the CPA was signed over four and a half years ago elections were a key element of the internationally supported strategy to set Sudan on a path toward democratic transformation. Elections offered hope of altering the predatory relationship between the repressive government in Khartoum and its marginalized peripheral populations, a dynamic that has plagued Sudan for much of its 52 years of independence and that remains at the root of its interlocking crises. Elections were also seen as a means to make administrative structures in the South more accountable and effective. Today Sudan’s coming elections are not as a whole a cause for hope, but instead a sobering microcosm of the challenges facing Sudan in the run up to the 2011 referendum. The elections still mark the beginning of a process that will durably alter the country’s history, but considering the current state of play, this process might lead to the violent dissolution of the Sudanese state.

Huge hurdles and bad precedents: The elections and the referendum

Enough recently argued that while the prospect of wholesale democratic transformation in Sudan through the 2010 elections is no longer realistic, holding elections on time and in a safe environment remain essential for avoiding the outright collapse of the CPA.1 However, as delays continue to plague the electoral process and deadlines pass largely without comment or action by the ruling parties, the prospect of holding these elections at all grows more daunting. Moreover, theses challenges set a dangerous precedent that directly affects the all-important final benchmark of the interim period of CPA implementation: the referendum for the self-determination of southern Sudan.

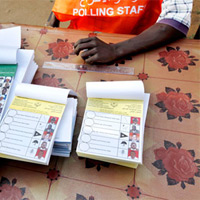

Daunting legal and logistical obstacles currently impede the electoral process. The National Elections Act, enacted in July 2008—more than two years after the date agreed to in the CPA—is vague on the policies and procedures for the elections and draft regulations have yet to be finalized. The National Assembly recently adopted highly questionable reforms to the Press and Media Law, and it has yet to amend the National Security Act, a law that bears directly on the safeguarding of civil liberties during the electoral process. Voter registration remains an enormous logistical challenge, as it will now be held during the rainy season, a time when most of the rural and remote areas of Sudan are largely inaccessible by road. With less than nine months remaining before the polling period begins, 20 million potential voters must be registered in a voter registration process that has not yet commenced. These voters, the majority of whom are illiterate and many of whom have never voted before, will then be asked to complete a complex and confusing series of ballots, casting their vote in local, regional, and national elections.

Meanwhile the ongoing dispute between the northern and southern governments over the results of Sudan’s census has blocked progress on the elections timetable and deepened the impasse between the North and South on the crucial issue of wealth and power sharing after the referendum.

One international specialist working on Sudan’s elections told Enough, “No one is paying attention [to the elections] right now, but in six months, people will be ringing the alarm bells. By then it will be too late.”

Potentially perilous elections will directly affect the self-determination referendum for southern Sudan, which politicians in both the North and South rightly view as an event with enormous ramifications. Unlike the elections, which were reluctantly accepted by the Sudanese parties at the behest of the international community (particularly the United States), the 2011 self-determination referendum for southern Sudan is the provision of the CPA that resonates most deeply with the southern Sudanese people. Although popular perceptions around elections are mixed, the National Democratic Institute’s focus group research, which has tracked opinions in the South since the CPA was signed in 2005, shows a consistent and overwhelming desire among southern Sudanese to vote for secession in the self-determination referendum. Southerners living in remote villages do not know the exact date when they will be able to vote in the referendum—in fact, this date has not yet been set because the referendum law has not been passed—but they know that the referendum “is coming” and significant delays are a potential trigger for future violence.

The consistent delays and lack of transparency in the electoral process have set a precedent that bodes poorly for timely organization of the referendum. The referendum law is unlikely to pass in Sudan’s National Assembly before the general elections, which opens the possibility of the NCP using a new and perhaps northern-dominated body to manipulate provisions of the CPA and further forestall the referendum. Elections would then give way to an increasingly tense and potentially explosive period: the “homestretch” between the elections and the referendum. At this point progress on the preparations for the referendum will indicate whether or not the NCP is likely to act as an honest broker and allow the referendum to occur without manipulation or interference. During this period power-sharing discussions with the South now occurring under the radar might come to a head, further increasing the stakes for both the NCP and the SPLM.

Future flashpoints: Unimplemented CPA provisions

Abyei: Abyei, the hotly contested, oil-producing zone which straddles the (as yet undemarcated) North-South border, is the subject of a distinct protocol in the CPA and has been considered a threat to the fragile North-South peace since the CPA was signed in 2005.2 Abyei has also been the site of multiple violations of the CPA-mandated ceasefire, most notably in May 2008, when an incident between the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, or SPLA and the Sudan Armed Forces, or SAF, led to a heavy bombardment of Abyei’s civilian areas, looting of markets and homes by SAF forces, and the displacement of the entire civilian population—an estimated 90,000 people—from the town itself. The NCP then took a particularly hostile attitude when it rejecting the findings of a commission created to determine Abyei’s contested border. On July 23, two years after the Abyei Boundary Commission issued its report, the Court of Arbitration in the Hague will issue its decision on the validity of the commission’s finding, a much-anticipated ruling that has implications for future wealth sharing between the North and the South and will determine who can vote in the referendum.

North-South border demarcation: Delayed demarcation of the border between northern and southern Sudan is further amplifying the pressures between the NCP and the SPLM. This provision of the CPA, which also involved an expert commission to determine where the North-South boundary should be drawn, has been delayed and disputed because of its direct impact on future oil revenue sharing between the North and the South. In the absence of border demarcation, a military build up has taken place in both the North and the South. Any decision on the border, which snakes through many of Sudan’s oil fields, will provoke strong reactions not only from the NCP and the SPLM, but also from armed tribal militia elements stationed along the demarcated line.

Joint Integrated Units, or JIUs: In February the NCP’s Sudan Armed Forces and the SPLA clashed in Malakal, a tense town in southern Sudan near significant oil reserves. The fighting highlighted flaws in the Joint Integrated Units, or JIUs, which were created by the CPA to encourage cooperation between the northern and southern armed forces. The JIUs were yet another belatedly implemented provision of the CPA and were never given joint doctrine or command-and-control structures. In places like Malakal, where the JIUs are largely composed of former warring militia who fought on opposite sides during the North-South conflict, their presence has led to greater violence, instability, and civilian casualties.

Intercommunal tensions and pervasive insecurity in the South

In the first half of 2009 more than 1,000 people have been killed and more than 135,000 displaced by interethnic and interclan fighting in southern Sudan. The death toll in the South now exceeds the number of violent deaths in Darfur during the same period, and as elections draw closer, violence and instability may well increase. Deadly cattle raids in Jonglei state, clashes between the nomadic Misseriya and Rizeigat in South Kordofan’s Nuba Mountains, and Bari-Mundari fighting outside the South’s capital, Juba, are indicative of the sharp uptick in both the scale and scope of the violence in recent months. Road banditry throughout the South, criminal activity in Juba, and the destabilizing presence of the Lord’s Resistance Army in Western Equatoria state further illustrate the myriad internal and external destabilizing factors threatening the increasingly fragile peace in southern Sudan.

Intercommunal violence is not a new phenomenon in southern Sudan. Cattle raiding and conflict over land and grazing rights frequently took place during the North-South war, when local conflict resolution mechanisms broke down. The CPA calls for a review of land policy and the creation of a land commission to address the enduring issues of land access and ownership at the root of much of the insecurity that persists in southern Sudan. Almost no progress has been made on implementing these provisions, and land and resource tensions remain at the heart of interethnic conflict. What’s worse, reports indicate that the violence now indiscriminately targets women, children, and the elderly, a disturbing shift in cultural behavior given that cattle raiding had traditionally occurred between young male warriors.

These tribal clashes occur among a heavily armed civilian population that the poorly disciplined southern army has proved incapable of securing. In a territory almost twice the size of France, which has not yet recovered from over two decades of war, it is difficult to overstate the challenges facing the fledgling Government of Southern Sudan on every front. Without a much more stable security situation, GoSS will continue to be incapable of making progress on building infrastructure and of improving its efforts to provide the “peace dividend” promised to its population by the CPA.

GoSS President and SPLM chairman Salva Kiir and other top GoSS officials have attributed the recent upsurge in violence to the NCP, claiming that the northern government is arming proxy militias throughout the South in an attempt to undermine the CPA. This development is not surprising given the NCP’s strategy of eroding confidence in the CPA through calculated and destabilizing actions. Furthermore, the accusations and back and forth regarding the recent violence have exacerbated the increasing tensions between the SPLM and NCP.

Meanwhile, the GoSS’ security problems are made worse by steadily declining oil revenues, which have cut the southern government’s budget—over 98 percent of which comes from oil—by more than half. Salaries for soldiers, teachers, and other civil servants have gone unpaid for the past several months. Even without the financial crisis, the remaining funds that might have been available for building much-needed infrastructure in the South, from roads to schools, are now likely being siphoned off in support of the central driving strategy of the GoSS: preparation for a serious confrontation—namely a return to war—with the northern government.

In this climate of insecurity, the United Nations Mission in Sudan, or UNMIS, has struggled to operationalize its core mandate: monitoring the ceasefire and security arrangements of the CPA. UNMIS has neither anticipated the recent outbreak of violence in the South, nor responded adequately in its aftermath. UNMIS’ relative timidity has gone beyond the limits of reasonable prudence, contributing to missed opportunities to use the mission’s extensive resources to coordinate local-level responses before, during, and after violence occurs, and to build local capacity to respond to these issues in the future.

Motivations and strategies of the parties

Enough has consistently argued that both the NCP and the SPLM will seek to use the elections to strengthen their positions prior to the 2011 referendum without precipitating a CPA’s premature collapse. These strategies may persist if both parties are able to achieve their desired outcomes without causing the other side to escalate in the tense run-up to the referendum. Recent actions by the NCP, however, have demonstrated a dangerous tendency toward brinksmanship. During confrontations in both Abyei and Malakal, the NCP seemed to be “testing” the limits of the SPLM, trying to determine how far they could push the Southerners without triggering an outright explosion. Unless the international guarantors of the CPA explicitly discourage such behavior on the part of Khartoum, war could easily result from unilateral defiance pushed one notch too far—a situation that neither of the two parties desires.

National Congress Party (NCP)

As the NCP approaches its twentieth year in power, the Khartoum regime continues to exercise its well-practiced “divide-and-rule” and “delay-and-distract” tactics to great effect. By creating multiple crises and challenges to distract and confuse both the SPLM—its “partner” in the CPA—and the international community, the NCP succeeds in stymieing efforts to fully implement the CPA without resorting to obvious signs of obstruction. The NCP’s subtle but persistent policies of intransigence are paying off in its success in delaying the electoral process, border demarcation, the referendum timeline, and other key provisions. These delays amount to a deliberate sabotage of the crucial CPA benchmarks that could prevent a return to war.

President Bashir recently criticized the SPLM for attempting to stifle political opposition in the South in the upcoming elections—a criticism that is mostly unsubstantiated. He threatened to punish the SPLM for its supposed repressive practices in the South by preventing the party from campaigning in the North. Bashir’s remarks served two purposes. First, Bashir anticipated criticism of a new political party in the South, a so-called “splinter” group of the SPLM led by Lam Akol, a former SPLA commander whose relations with the Khartoum regime during and after the war led to his falling out with the mainstream SPLM. Bashir opened space for Akol’s new party, called “SPLM-Democratic Change,” to begin a campaign to openly criticize and undermine the SPLM. This effort is unfortunately well positioned to take advantage of the SPLM’s widespread criticisms for large-scale corruption. Second, Bashir threatened the SPLM’s legitimate right to campaign in the North under the pretext of concern about the ability of opposition groups to campaign in the South.

The NCP is more constrained than ever due to the International Criminal Court’s recent issuance of an arrest warrant for its leader, President Bashir. However, the warrant has not slowed the NCP’s efforts to remain the one and only electoral partner of the SPLM in the North . The NCP’s eagerness for political partnership with the SPLM, which is closely related to their desire to marginalize the Northern opposition parties, should be used to extract from the Islamist party a minimum engagement toward electoral freedom next year. At present there is no sign that any of the main actors has adopted this strategy.

Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM)

The SPLM is outwardly campaigning for the elections as a national party that has a legitimate chance of winning the Government of National Unity presidency. By aiming to wrest control of the central state from the predatory NCP, the SPLM argues that it can preserve its former charismatic leader John Garang’s vision of unity in a “New Sudan.” This vision, however, is unrealistic for a number of reasons, central among them that most southerners no longer support the concept of unity and are unlikely to support it as the SPLM’s political strategy. The deep-seated anger and historical resentment of southerners toward the NCP has not changed significantly during the CPA’s interim period.

In the North, regardless of widespread dissatisfaction with the NCP, the majority Muslim population is unlikely to vote for the SPLM, a party viewed in the North as Christian. Regardless of its external posturing, it is less than sure that the SPLM will push its leader, Salva Kiir, into the national presidential race. A presidential race in which the SPLM was represented by a symbolic candidate without realistic hope of victory would only reinforce the feeling of southern alienation and separateness. At present, everything points to a disconnect between the SPLM political elite—who still pursue a dream of winning a national victory—and a southern public which either does not believe its party can win nationally or does not care about the elections and only aims for meaningful participation in the self-determination referendum.

Preventing a return to war: recommendations

The myriad challenges and risks facing Sudan in the next 19 months cannot be addressed and mitigated unless the international community adopts a new approach to the crucial final stages of CPA implementation. Robust, coordinated, and high-level engagement is essential from all, not just a few, of the CPA’s “guarantors”—those states and organizations that witnessed the signing of the CPA and agreed to support its implementation.3 The United States and other key guarantors should play a lead role in driving this multilateral, multi-track approach, since the scale of the challenges over the coming months merit the engagement of all of the international actors who committed four years ago to supporting implementation of the CPA. This week’s Washington conference is a positive start, but should be followed-up with efforts that penalize failure to implement key provisions of the agreement. Engagement must avoid a myopic focus on the current problems and instead consider longer-term policy objectives that, after the referendum, will help prevent a violent collapse of the Sudanese state.

The international community must direct renewed energy and commitment in the remaining interim period of CPA implementation toward the following strategic priorities:

- Treat Sudan’s problems holistically and prioritize CPA implementation as the central means of addressing the roots causes of Sudan’s conflicts. The framework of the CPA was designed to address the root causes of Sudan’s interrelated conflicts, and it is the only existing agreement that addresses disparate but interconnected issues, from land conflict to armed militias, in a coordinated manner. Prioritizing CPA implementation today means understanding that Sudan’s problems are not isolated from each other. Pursuing an all-Sudan solution means working to build the peace fostered by the CPA between the North and South while simultaneously engaging in coordinated diplomatic efforts to end the war in Darfur and enable internally displaced people and refugees to return home. Furthermore, the international community should make it clear that there will be costs if the parties to the CPA, particularly the NCP, do not abide by their commitments. Without movement on this issue, the basic facts on the ground will not change.

-

Encourage passage of the referendum law before the elections. Applying pressure on the Government of National Unity to urge the National Assembly to review and pass the law on the southern referendum before the elections could reduce tensions between the parties after the elections and enable preparations for the referendum to begin now. Once the law is passed and the Referendum Commission is created, potential disputes, such as questions over whether or not certain populations—such as southerners in Khartoum—are eligible to vote, can be addressed before tensions escalate in the immediate run-up to the referendum.

-

Focus U.N. efforts on establishing security at the local level through robust monitoring and coordination. UNMIS should play a much more proactive role in monitoring ceasefire violations by engaging with local actors to prevent violence through more robust conflict resolution programs and through rapid response teams that can quickly deploy in instances of outbreaks of violence during the electoral process. By improving information sharing and analysis at the local level and establishing dynamic military and civilian presences in tense areas, UNMIS can better develop response and protection strategies to prevent and mitigate future violence. The United States should lead efforts within the Security Council to strengthen UNMIS’ ability to support the CPA, but this support must be matched with clearer strategic vision by UNMIS on how it can best allocate its resources to operationalize its mandate amidst ongoing security threats throughout the South. Other guarantors of the CPA can support UNMIS’ efforts by contributing to coordinated programs such as security sector reform within the SPLA and by providing donor support to other programs to enable GoSS to address multiple internal security challenges.

-

Develop coordinated short-term and long-term policy strategies on key questions. Each guarantor of the CPA must answer several important questions regarding their government’s or organization’s policy on the remaining CPA interim period and any post-referendum scenarios. Convening policy task forces in each country and reconvening the guarantors frequently to discuss priorities and areas of concern in the remainder of the period can help clarify strategies. Coordination and regular communication with the Assessment and Evaluation Commission—a group composed of representatives from the NCP, SPLM as well as Kenya, Ethiopia, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Norway, and Italy tasked with monitoring CPA implementation—is essential to monitoring progress and breaking developments on the ground, as will regular ad hoc consultations at a more senior political level. Existing diplomatic resources, such as U.S. Special Envoy to Sudan Major General Scott Gration and his counterparts in the United Kingdom among other partners, should be mobilized to lead these coordinating efforts and present a united front in negotiations with the NCP and SPLM.

- Encourage negotiations between the NCP and SPLM on long-term wealth-sharing arrangements before the 2011 referendum. Track-two diplomatic efforts can get both parties to consider various scenarios for wealth sharing after the referendum and mitigate the likelihood that these discussions will short circuit into a zero-sum game leading directly to conflict after the referendum. Discussions of access to land for populations with diverse needs and livelihoods and planning for mutually beneficial development of oilfields in the contested border region could ease current tensions over border demarcation and generate momentum for further cooperation.