Download the full report here.

Download the full report here.

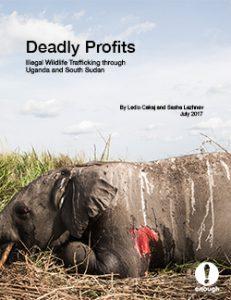

Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs.

In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant population in Congo has decreased by an estimated 75 percent since 1996 mainly due to poaching, according to park officials in Congo. Since conflict broke out in South Sudan in December 2013, South Sudanese poachers and armed groups have increasingly crossed into Garamba park in Congo, for example, through the little monitored Lantoto National Park in South Sudan, and likely now make up the majority of poachers there, according to park officials and United Nations experts. Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), armed Sudanese poachers, and Mbororo pastoralists in Congo also continue to poach in Garamba.

South Sudanese poachers in Congo appear to be a mix of soldiers, former soldiers, police officers, and civilians, based on Enough Project field interviews. They traffic ivory and other wildlife to foreign markets via smuggling routes, mainly through South Sudan, particularly Juba International Airport and/or by road through neighboring Uganda, an important transit point for trafficked animals and ivory tusks originating from Congo and South Sudan. Insecurity in South Sudan has helped create an ivory trafficking route from the southwest of South Sudan eastward to Juba. From there, it is either flown out of the country via Juba Airport or driven south to Uganda via the border crossings at Nimule or Oraba. Over five tons of ivory was seized at Juba’s airport in 2014-15 alone.

Based on estimates from seizures in Uganda and interviews with experts in Congo, South Sudan, and Uganda, large amounts of ivory from Garamba are transported to Uganda either through South Sudan or via Congo-Uganda border crossings. Elephant ivory fetches up to $250 per kilogram ($113 per pound) in the Ugandan black market, a significant amount of money locally. The wildlife is then trafficked to either Entebbe International Airport or the border crossings between Uganda and Kenya and to the Kenyan port of Mombasa, which is another exit point of illicit goods destined for Asian markets, or to the port of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

The Ugandan government has recently taken important measures to address the problem. Recent efforts include setting up a court dedicated to wildlife crimes, ordering investigations into the leadership of the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) for the alleged theft of ivory from its storerooms and other alleged offenses, completing the review of the 20-year-old Uganda Wildlife Act that will now be sent to the Parliament of Uganda, beefing up penalties for poaching and trafficking, and increasing the number of wildlife seizures, arrests, and prosecutions in recent years. However, organized criminal groups are likely still involved in trafficking in Uganda. International traffickers continue to use Uganda as a waypoint, as evidenced by the February 2017 seizure of over one ton of ivory suspected to be from neighboring countries and the arrest of three West Africans near Kampala. Also, UWA officials are accused of attempted bribery of banks, which UWA denies. And while a new court dedicated to wildlife prosecutions is an important step, there is only one such court in the country, and prosecutions of high-level traffickers have been limited to date. One problem has been the storage of seized wildlife and the subsequent trafficking of it. For example, in October 2014 an internal audit of the Uganda Wildlife Authority’s stock room found that 1.35 metric tons of elephant ivory had gone missing from 2009 to 2014. International authorities increasingly recognize Uganda as a wildlife trafficking hub. Although the Ugandan government has taken several key anti-poaching and trafficking steps within the last year, much remains to be done to combat trafficking. Uganda was listed as one of ten countries worldwide “linked to the greatest illegal ivory trade flows since 2012,” including those from Central Africa, according to the global body that tracks poaching and trafficking, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Trafficking through Uganda appeared to worsen with CITES listing it for the first time in 2013 as a country of “primary concern.”

Furthermore, there have also been several cases of state-affiliated actors involved in wildlife trafficking in Uganda and South Sudan. Some of these cases have been prosecuted, e.g., a February 2017 conviction of mid-level Ugandan army officers for ivory trafficking. However, several cases have either not been prosecuted or have lingered in the Ugandan court system for years, and there have been no convictions to date for the missing 1.35 tons of ivory first reported three years ago. In South Sudan and Uganda, there has been little accountability to date for high-level cases of officials involved in trafficking. In some cases, in South Sudan, traffickers were released or never charged. In addition, storerooms in Uganda for wildlife artifacts confiscated from smugglers appear, in some instances, to be sources for further black-market trade.

Understanding and combating trafficking in South Sudan and Uganda should be of primary importance to policymakers aiming to curb the frenzied levels of poaching in one of Central Africa’s remaining sanctuaries for wildlife, Garamba National Park. To this end, the following authorities and offices should fully consider and implement wherever possible the recommendations as follows:

Recommendations

- Increase accountability. The United States and European nations should urge the Ugandan government to follow up on high-level cases of wildlife trafficking in Uganda’s military, anti-corruption, or wildlife courts, as well as cases in South Sudanese courts, to help ensure that the cases move forward in their respective justice systems. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), Denmark’s Danida, and other donors should provide assistance to the Ugandan Ministry of Justice to expand the wildlife court and train judges in wildlife crimes. Training should include how to properly value wildlife, such that judicial sentences are appropriate to the scope of crimes committed.

- Combat poaching in and around Garamba. With U.S. Congressional support, the U.S. Department of Defense should authorize funding to support Garamba National Park rangers and African Parks (the NGO which manages the park) to help interdict the illegal poaching and wildlife trade from Congo to South Sudan and Sudan. For example, with additional funding, AFRICOM could help provide technology to augment park rangers’ interdiction capability, such as night vision, thermal recognition, camera traps, and night-flying panels for helicopters over Garamba park. European military personnel and contractors, MONUSCO, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service could also provide assistance. MONUSCO peacekeepers could also, in collaboration with FARDC military or Congolese police, conduct ‘stop and search’ operations of trucks suspected of transporting ivory by road.

- Follow the money. Justice authorities in the European Union, the United States, Uganda, and elsewhere with jurisdiction over individuals and companies suspected of high-level involvement in illegal ivory trafficking should investigate the most serious cases of trafficking, money laundering, and other related crimes. Financial intelligence units in the United States and Europe, banks, and other financial institutions should build on the study produced in mid-2016 by the Eastern and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG) to combat the laundering of the proceeds of trafficking through the international financial system. Sanctions authorities such as the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) should pursue and designate key traffickers and their criminal networks.

- Maintain wildlife stocks. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and European states should provide technical assistance to the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) to ensure that wildlife stocks are kept safely in one or two depots, under the sole control and responsibility of UWA executives.

- Pass legislation with harsher penalties. The Parliament of Uganda should pass the revised Wildlife Act, which includes stiffer penalties for wildlife trafficking, that the Ugandan cabinet has now finished reviewing.

- Support local anti-trafficking groups. International donors and conservation authorities should increase support to local organizations in Congo, South Sudan, and Uganda that carry out investigations of wildlife trafficking. Public-private partnerships may be applicable here.