In its Sudan policy review completed in mid-October 2009, the Obama administration indicated it would regularly assess the progress of peace in Sudan—or lack thereof. Administration officials have stated that the parties to Sudan’s multiple conflicts will be under the microscope, and held to clear and pre-determined benchmarks of progress. The relative progress on these benchmarks would then determine the pressures and incentives—so-called “carrots” and “sticks”—that would be brought to bear in 2010, a year the Obama administration itself said, “can either lead to steady improvements in the lives of the Sudanese people or degenerate into even more violent conflict and state failure.”

To date, the Obama administration has not publicly disclosed the precise benchmarks it is applying to assess progress in Sudan, even as the official review process takes place this month and as tensions increase with the April national elections and January 2011 referendum on independence for southern Sudan rapidly approaching. To help bring transparency to the process by which the United States ensures strict adherence to unambiguous benchmarks, and ensure that the appropriate pressures and incentives are applied accordingly, this paper aims to provide guidance for how officials, concerned citizens, and others in the international community can assess genuine progress toward a lasting peace in Sudan.

Continue reading the full benchmarks paper.

In a live, follow-up interview to his State of the Union address, President Obama answered questions submitted and voted on by YouTube users. Recognizing the opportunity to reach President Obama directly on the issue of Sudan, the Enough Project submitted its own video question. Here is the President’s response:

TAKE ACTION

To: Erica Barks-Ruggles, Tom Donilon, Jim Steinberg, Stuart Levy, and Michele Flournoy:

When the National Security Council Deputies Committee committee met in January to review progress of the Obama Administration's Sudan policy, I was hopeful that you would act decisively in leading other countries to hold those who promote violence in Sudan accountable.

I was disappointed that you did not publicly or transparently disclose the outcomes of your meeting. And the conflicts across Sudan are getting worse as we inch closer towards the elections in April. The U.S. government has not made the progress necessary to broker agreements in Sudan that will stabilize the country.

I therefore urge you to escalate real pressures on the parties, support an international surge to protect civilians during the election period, and immediately deploy full-time U.S. diplomatic teams to the region in order to accelerate peace efforts. Only with increased pressures and a full-time field-based diplomatic presence in Sudan, working on both Darfur and the North-South issues, will peace efforts have a chance of success.

[pagebreak]

Policy paper by Enough Co-founder John Prendergast

Introduction

In its Sudan policy review completed in mid-October 2009, the Obama administration indicated it would regularly assess the progress of peace in Sudan—or lack thereof. Administration officials have stated that the parties to Sudan’s multiple conflicts will be under the microscope, and held to clear and pre-determined benchmarks of progress. The relative progress on these benchmarks would then determine the pressures and incentives—so-called “carrots” and “sticks”—that would be brought to bear in 2010, a year the Obama administration itself said, “can either lead to steady improvements in the lives of the Sudanese people or degenerate into even more violent conflict and state failure.”

To date, the Obama administration has not publicly disclosed the precise benchmarks it is applying to assess progress in Sudan, even as the official review process takes place this month and as tensions increase with the April national elections and January 2011 referendum on independence for southern Sudan rapidly approaching. To help bring transparency to the process by which the United States ensures strict adherence to unambiguous benchmarks, and ensure that the appropriate pressures and incentives are applied accordingly, this paper aims to provide guidance for how officials, concerned citizens, and others in the international community can assess genuine progress toward a lasting peace in Sudan.

Background: The Obama Administration’s clear statement of intent

The administration was clear in October 2009 that these benchmarks had to reflect substantive achievements in Sudan, not just rhetoric:

“Assessments of progress and decisions regarding incentives and disincentives must not be based on process-related accomplishments (i.e. the signing of a MOU or the issuance of a set of visas), but rather based on verifiable changes in conditions on the ground.”

The administration also spelled out an explicit process for measuring progress, built around quarterly reviews by deputies from a variety of agencies. Each quarter, and beginning this month, senior-level staff from various agencies are tasked with measuring progress in Sudan against a variety of indicators. A failure to improve conditions, the administration has said, “will trigger increased pressure on recalcitrant actors.”

As noted, the administration has chosen to keep the benchmarks it is utilizing in assessing progress in Sudan opaque. Neither the benchmarks themselves, nor the pressures and incentives that are to be deployed in response, are public. There are understandable reasons why the administration would choose to keep these protocols classified. However there appears to be some confusion within the U.S. government about the nature of these classified protocols and their use. Such confusion is concerning, because the administration must stick to its public commitment to review progress in Sudan and respond accordingly.

Success relies heavily on a consistent strategy of holding the parties in Sudan accountable for their actions. As President Obama said in accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, “When there is genocide in Darfur, systematic rape in Congo, repression in Burma—there must be consequences. Yes, there will be engagement; yes, there will be diplomacy—but there must be consequences when those things fail.”

The U.S. policy will only be effective if the administration is vigilant in responding to progress or a lack thereof. Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir is being sought by the International Criminal Court for war crimes. The U.S. government continues to declare that genocide is ongoing in Darfur. Holding to the benchmarks as laid out by the administration is crucial. Anything less would send a dangerous message to those perpetrating violence in Sudan that they can continue to act with the same impunity they have enjoyed in the past. Protecting Sudan’s civilians in this volatile and historic period is absolutely essential.

How can relative progress in Sudan be accurately assessed? There are a number of factors that should be considered in any principled set of benchmarks and watched closely over the next year. There is broad agreement among Sudanese and those concerned with the fate of Sudan that these benchmarks constitute the fundamental elements of a durable peace and serve as key indicators of progress toward that peace. In order to achieve a sustainable peace and avoid a return to war, all parties in Sudan must address these core issues.

[pagebreak]

The Benchmarks

National Reforms

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement, or CPA, contained key elements that were intended to transform Sudanese society, allow greater respect for civil liberties, and make unity more attractive to southern Sudan. This agenda offered the greatest promise for changing how Sudan is governed in fundamental ways and resolving the root causes of the country’s cycle of conflict between the center and the peripheries. The CPA should have ushered in greater press freedoms, expanded political space for civil society and opposition, reformed the national civil service, provided greater fiscal and governance autonomy to the states, and eliminated laws permitting detention without trial. Unfortunately, these critical provisions of the CPA have often been swept under the rug by the parties themselves and by international diplomats as they have pursued specific tactical goals in subsequent negotiations.

Progress on these national reforms is crucial for long-term peace in Sudan. Without addressing the repressive dynamic of concentrating power and wealth in the center at the expense of peoples in the peripheries, peace in Sudan will remain illusory whatever the outcome of the southern referendum in 2011. The likely southern vote for secession will not solve the problems of Sudan; the South will simply be opting out of them. Even if there were a peace agreement in Darfur tomorrow, the imbalance of power in Sudan and the systematic denial of fundamental human rights would likely lead to new conflicts in the North, South, East, the Nuba mountains, Southern Kordofan, Blue Nile, and elsewhere in the country.

The CPA offers entry points for essential national reforms in advance of the national elections in April 2010 and southern Sudan’s self-determination referendum in 2011. While international assistance has focused a great deal on the mechanics of balloting, very few donors have been willing to state publicly that a conducive environment for free and fair elections does not currently exist, and without that conducive environment technical assistance will only result in a rubber stamped process that could easily trigger new violence.

The passage of a national security law that grants extensive powers to the security services to arrest and detain citizens without charge, and the use of violence by government security forces against peaceful political demonstrations in December 2009 are clear indicators that the benchmarks for national reform have not been met. In December the parties agreed to pass some key laws, however we would urge the United States to pressure the Sudanese government to revise the flawed national security act, trade unions act, and make amendments to the criminal law among others.

Key benchmarks include:

- Discontinuation of the use of the national security law to arrest or otherwise intimidate civil society, human rights activists, and political actors.

- Peaceful demonstrations and other gatherings allowed without interference.

- Freedom for candidates for public office to campaign without intimidation.

- Concrete measures taken in Khartoum and Juba to ensure freedom of the press and freedom of association.

Security

The broad security environment in southern Sudan, in Darfur and even the capital, Khartoum, should all be considered as key measures of how the parties in Sudan are behaving. There have been a number of deeply concerning developments on this front. Recent opposition protests in Khartoum have been violently halted by the authorities, illuminating the stark lack of individual security as well as the stalled or absent nature of the aforementioned national reforms.

The U.S. Special Envoy has achieved some important successes in tamping down cross-border incursions between Chad and Sudan, but a recent report by the UN group of experts made clear that the UN arms embargo continues to be widely flouted, including by the NCP and Darfur rebel groups. Respect for the arms embargo should be considered a key benchmark, and stronger enforcement by the UN Security Council is an important step towards improving the security environment.

A functioning ceasefire in Darfur will also be a key benchmark of progress – as long as this ceasefire is also tied to a viable and advancing peace process.

Over the long term, there is probably no better barometer for the relative success or failure of the international community than the circumstances of the almost 3 million people who remain displaced or refugees after having been forced to flee from their homes by the government and its allied janjaweed militias. Darfuris are desperate to return home from camps for refugees and the internally displaced, but will only do so if they feel secure. In recent months, the NCP has announced its intention to close down internally displaced persons camps, despite the lack of security.

The NCP should be creating an environment in which returns may occur voluntarily and safely, in keeping with the rights of refugees and displaced persons, and its performance in this regard should be one key measure of progress. The government should also provide restitution for damages and resolution of disputes regarding land rights, since many villages were destroyed and are now reoccupied.

Violence in southern Sudan escalated sharply in the past year, with reports of inter-communal clashes whose intensity and casualties are far more serious than the South’s traditional cattle raids and which triggered significant displacement of civilians. The use of sophisticated weaponry during attacks that deliberately target civilians should raise alarm bells, given the long history of politicization of inter-ethnic conflict in southern Sudan. It also highlights the need for increased attention on security sector reform in the South and attention to the often-violent civilian disarmament campaigns in the South. A recent increase of activity in southern Sudan by the Lord’s Resistance Army, or LRA, is another warning sign. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, or SPLM, has accused the NCP of supporting proxy militias and stoking inter-communal tensions, and based on the NCP’s history the United States and others must evaluate these claims very seriously.

Some other key indicators on the security front also include:

- Negotiation and implementation of a functioning ceasefire in Darfur.

- An end to all provision of weapons, training, or supplies of financing to paramilitary militia groups in the North, South, or Darfur.

- Full cooperation from all parties to facilitate UN peacekeepers’ freedom of movement and other essential conditions to do their work effectively.

- Full compliance by all relevant parties with the UN arms embargo for Darfur.

- An end to unlawful aerial bombardment in Darfur.

- Increased peace-building efforts by the Government of Southern Sudan to prevent escalation of chronic inter-ethnic fighting.

- Standard, clear policies by the SPLA on engagement in tribal conflict, including the respective roles and responsibilities of the army and police services.

- Disarmament campaign carried out responsibly by SPLA in consultation with local communities.

Humanitarian access

While a few of the aid agencies that were expelled from Darfur were allowed to return by the Sudanese government, it is clear that no party can be seen as acting in good faith with regard to existing agreements if humanitarian aid is systematically denied to a population. Right now, the protection sector has been effectively neutered by the NCP. For example, women do not have access to services to deal with sexual and gender-based violence.

To ensure that aid is actually reaching those who need it most, not only do aid organizations need to be let into Darfur, they need to be able to move freely and reach their target populations. Any effort to systematically deny assistance to victims of gender-based violence should also be seen as a powerful and negative benchmark. Another important benchmark is whether the national and state governments are taking concrete steps to curb the spike in attacks and kidnappings of humanitarian workers.

As the administration considers the state of affairs in Sudan, it should assess the current state of humanitarian access, or lack thereof, by engaging with UNAMID and relief agencies operating in Darfur and determining whether or not the NCP or others are obstructing the rights of civilians to access all forms of humanitarian assistance. Any obstruction should trigger immediate consequences from the United States and its allies.

Key benchmarks to consider include:

- Agreements to facilitate humanitarian access are being respected and implemented.

- Improvement in security for humanitarian organizations, and steps taken to investigate and prosecute attacks on these organizations.

- Delivery of sufficient aid, and access for new humanitarian NGOs, as needed, to reach vulnerable populations.

- Freedom for humanitarian organizations to report honestly on conditions on the ground.

- Aid agencies allowed to fully implement programs assisting women who have been victims of sexual violence or other forms of abuse.

Darfur Peace Process

Given the interrelated nature of Sudan’s multiple crises, the state of the Darfur peace process should be considered as a barometer of the overall process in Sudan. Although the NCP has stated that it is willing to negotiate, it has failed to adhere to multiple commitments in Darfur and the current process lacks the credibility needed to attract all parties to the table. The United States and other external actors, therefore, should construct a viable process and press the Sudanese government, rebel groups, and key civil society actors to come to the table and negotiate in good faith.

Experts have already outlined a way forward for the Darfur peace process thatc calls for the United States and others to work with the joint United Nations/African Union mediation team to put forward a common framework for a peace agreement. In the interim, efforts should continue to unify various rebel movements and to allow independent civil society groups to reach broad consensus on a position for negotiations.

Key steps for a just and sustainable peace that policymakers should be looking for include:

- Establishment of an inclusive peace process.

- Pre-existing commitments made in earlier talks and agreements fulfilled by the parties.

- Practical steps on the ground taken by parties to promote peace and improve security.

- Credible and independent civil society groups allowed to freely participate in the peace process without obstruction of their travel or right to assemble.

- Concrete steps toward accountability for crimes committed in Darfur, including prosecution of soldiers, militia, and rebels who perpetrated attacks on civilians.

Abyei

Despite the NCP and SPLM’s stated acceptance of the ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, or PCA, on the boundary of Abyei, this oil-rich region remains a major flashpoint. The signs are not good. The committee established to oversee implementation of the ruling, has been unable to fully demarcate the border because of political obstruction. The government has not transferred funds needed for development, and many people displaced in the May 2008 clashes have not yet returned. Both parties need to do more to prevent conflict in Abyei and to ensure that its residents are allowed to vote in a self-determination referendum in 2011. These include the following:

- Rapid and mutually agreed upon formation of the Abyei referendum commission.

- Full implementation of the Abyei Protocol and PCA’s ruling.

- Unreserved support for demarcation of the border.

- Support for a process to develop guarantees for nomadic tribes to access traditional grazing lands.

- Development of the popular consultation process (see below) to promote popular political transition in Southern Kordofan.

- Improved monitoring of Abyei’s oil revenues, payment of past arrears from Khartoum to Juba, and transparent functioning of the Unity Fund.

[pagebreak]

.

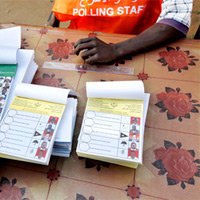

Elections

The April 2010 election will be a key test for all of the parties to Sudan’s multiple conflicts. Although the elections are less than 90 days away, the environment for them to be free and fair does not exist. In the northern states, security forces have continued to crack down on opposition parties and activists. In Darfur, a large military presence and ongoing insecurity is likely to prevent people from voting freely – if at all.

While the SPLM and the NCP appear willing to bargain with regard to the 2010 elections, it is vital that the administration take a critical look at violence around the election, the ability of candidates from all parties to campaign effectively, freedom of the press and assembly, as well as vote buying, intimidation, and other efforts to manipulate popular will. Moreover, given the prevailing security conditions in Darfur, it is also challenging to imagine how Darfuris will see their rights of enfranchisement respected. There are widespread concerns that a vote held in April 2010 would only serve to disenfranchise huge number of Darfuris while making it more difficult for them to reclaim the rights to lands from which they were forced.

If the election is not credible, the United States and others must be prepared to not recognize the results and impose a clear cost on those who denied the Sudanese the right to elect their leaders.

Other key benchmarks in the run-up toward the elections include:

- Sudan’s constitutional protections of freedoms of assembly and expression ensured by the NCP and SPLM in the context of the current electoral process in northern and southern Sudan, respectively.

- Sudanese media free to cover and report on election related events, trends, and developments.

- Effective response by Sudan’s National Electoral Commission, or NEC, to concerns expressed by international and domestic monitoring bodies – including political party representatives – during the voter registration process in order to prepare for the polling period in April, including investigating claims of fraud.

- International and domestic monitors granted freedom of movement and freedom to report on election related activities in the coming months.

- Concerted steps by the NCP and SPLM to prevent electoral violence.

- Active measures by the NEC to educate Sudanese voters on the electoral process, particularly in areas with comparatively low levels of voter registration.

Popular Consultations

The popular consultations for Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states will be crucial in determining whether peace holds in these strategic border regions. Renewed conflict in either region could quickly spread, and carries a high risk of escalating along broader North-South lines because of the local SPLA forces from these areas. These processes must live up to their name – to be both popular and consultative – for the citizens from these states to feel they have a genuine stake in their political future. The recent passing of the population consultation law is a positive step, but much remains to be done in a short time frame for this process to succeed.

The administration should closely monitor the preparations underway in both states, and determine whether the parties are providing the necessary political space and requisite security for communities to peacefully learn and engage in the popular consultation processes. As the popular consultations are meant to be carried out by the newly elected state legislatures, contingency planning should also be encouraged to explore alternatives to support these processes if elections do not take place as planned.

Necessary steps for peaceful and successful popular consultations, and sustainable peace in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, include the following:

- Progress on the demarcation of the Abyei and North/South borders, including resolution of border disputes on southern borders of Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile.

- Processes for broad engagement with constituencies throughout the two states.

- Improved integration of the Joint/Integrated Units, police, and state administrations.

- Political space and security for free and fair elections.

Southern Referendum

The agreements reached between the NCP and the SPLM on a package of laws related to the upcoming election and referendum are important steps, but do not outweigh the accumulated actions over previous months. It is crucial to remember that in its 20-year and counting rule of Sudan, the NCP has signed numerous agreements and has always been slow, if not entirely unwilling, to implement them. Even the recently announced agreements again deferred discussions of key elements related to the referendum to a later date, highlighting the dramatic mistrust between the lead parties. In terms of benchmarks, key steps and questions for the coming year include:

- Rapid and mutually agreed upon formation of the southern Sudan referendum commission.

- Progress toward the full demarcation of the North-South border.

- No use of direct or proxy violence in an effort to derail the referendum.

- No actions that subvert the will of the people in casting their votes freely.

- Neither party negotiating in such a way that makes direct North-South violence more likely.

It is important to not simply make it to the referendum without war breaking out and keeping the existing peace agreement intact, but also to have a series of agreements in place for the days, months, and years after the referendum – on borders, revenue sharing, assets, water rights, and the many other factors that could precipitate a return to conflict. The willingness and ability of the parties to credibly engage in these post-referendum vote discussions in good faith should also be considered a key benchmark.

Accountability

As much as some would like to push accountability for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Sudan aside, to do so would neither be productive nor right. The policy review the Obama administration produced made the case that without accountability in Sudan, peace will likely prove elusive. The International Criminal Court, or ICC, has found sufficient evidence against Sudan's president, Omar al-Bashir, to accuse him of multiple counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Yet the ICC will only ever deal with a handful of individuals. Combating the culture of impunity in Sudan is a basic prerequisite to sustainable peace. Any disucssion of progress in Sudan should consider:

- Cooperation with the ICC or agreement to a robust accountability mechanism, such as the African Union’s recently proposed hybrid court for Darfur.

Conclusion

It is clear that the Obama administration will also consider Khartoum’s cooperation on counter-terrorism issues as another key benchmark for its performance. However, given the largely non-transparent nature of this indicator, we did not include it in our list above. It is important to note that although the administration’s own policy statements have noted that counter-terrorism cooperation is one of a number of factors being included in its internal evaluation, this priority does not preclude the importance of significant progress on other fronts.

The Obama administration has rightly demanded an approach to Sudan that is based on demonstrable change on the ground. Just as the administration has made clear that it will hold the parties in Sudan accountable for their actions, so too will activists and policymakers hold the Obama administration accountable for whether and how it consistently uses benchmarks to deploy pressures and incentives.