The Save Darfur Coalition’s Alex Meixner wrote this post, which originally appeared on SDC’s blog.

The first time I saw Manute Bol in person, I stared in something like disbelief. Bol and his Golden State Warriors were in L.A. to play the defending champion Lakers in the late 1980s, and even amid nine other professional basketball players, he literally stood out, easily a head taller than anyone else on the floor. And yet his decidedly un-Shaq-like physique made him seem somehow as vulnerable as he was imposing. In short, he was something of a wonder to behold, and his incongruousness with even his American counterparts gave 10-year-old me the briefest sense that the world was a very big place indeed.

In the following years, while I (like so many other Americans) saw my awareness of Sudan slowly grow from non-existent to minor, Bol continued to be perhaps the most-recognizable representative and benefactor of the millions of southern Sudanese who were living through a seemingly never-ending and atrocity-laden civil war. He made a fortune blocking shots in the NBA, and gave almost all of it away to help folks back home who needed it more. He offered up his body and what some would mistake for his pride by agreeing to be paraded out in front of gawking crowds in one-time fast-cash gimmicks. He laced up a pair of skates for a minor league hockey team (as you might guess, ice hockey isn’t a big pastime in Sudan) and soundly beat William “the Refrigerator” Perry in a celebrity boxing match.

Then, in 2004, while asleep in the back seat of a cab on the way home from the airport, his drunken driver lost control and crashed into the guardrail, killing himself and throwing Manute from the car. It would take him months to recover from a broken neck and other injuries, which combined with worsening rheumatism and a rare skin disease to make life even harder for the one-time athlete who had famously killed a lion with a spear while still in his youth and played 10 seasons in the NBA.

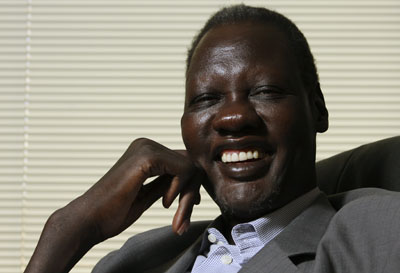

It was a bit less than two years after the crash that I once again found myself staring with some disbelief at Manute as he climbed out of a car into which I wouldn’t have thought he possibly could have fit just prior to Save Darfur’s rally on the National Mall in Washington, DC on April 30, 2006. To anyone armed with knowledge of his personal story and current circumstances, it was clear that his commitment to helping the people of Sudan was simply incredible. Despite his chronic ailments and recent injuries, despite the fact that he had had every opportunity to put himself first and walk off into a comfortable retirement, and perhaps most remarkably despite the fact that Sudanese President al-Bashir had for decades used Darfurian draftees to fight Bol’s tribesmen in southern Sudan (in much the same way Bashir later used members of these same tribes again by turning them into Janjaweed militias and setting them against their fellow Darfurians), this unassuming giant (and it’s not easy to pull off “unassuming” when you’re 7’7”) was once again giving all that he had left – his voice – to help Darfurian victims of the Sudanese government’s brutality. Throughout what were the last years of his life, his commitment never wavered.

Manute Bol was truly a walking, talking, larger-than-life object lesson in how to put God’s gifts to their best use. While he will likely be remembered here in America primarily for blocking shots and hitting improbable three-pointers, his true legacy is much bigger than that.

My colleague Niemat Ahmadi from Kabkabiya, Darfur in western Sudan says it best:

“He has become our voice, the voice of all the oppressed in Sudan. He was the pride of our country and will remain so. We are saddened that he has left before seeing the long awaited dream of every southerner in Sudan for the 2011 referendum, yet his light will continue to shine among us. We are all indebted to his courage, resolve and commitment that has inspired us and we will continue carry on the mission that he has started.”

Manute Bol died on Saturday, June 19, 2010 from acute kidney failure brought on by complications arising from his skin disorder, Stevens–Johnson syndrome. He was 47.