This op-ed originally appeared on Global Post and on CNN’s Global Public Square blog.

KAMPALA, Uganda — Since late 2010, the Central African Republic army has deployed two soldiers in a remote area of the country’s southeast to pursue the Lord’s Resistance Army, or LRA.

The destitute conditions of their mission illustrate one of the biggest challenges in the effort to end the 25-year conflict that has devastated parts of Central and East Africa.

The two soldiers were sent without any supplies. They spent most of their time collecting firewood and food, while surviving largely on humanitarian aid and provisions given by the Ugandan army. The one radio they had could be turned on just once a day, due to limited power from a small solar panel.

The reported capture (some say surrender) of LRA commander Caesar Acellam near the Congo-CAR border on May 12 could signal the beginning of the end of the LRA, but only if a number of things change.

Efforts to terminate the LRA remain vastly under-resourced.

In a significant step forward last year, President Obama deployed U.S. military advisors to provide advice and information to the region’s national militaries, and he announced in late April that they would stay for at least another few months.

Although Acellam’s capture is a major accomplishment, the overall picture remains bleak, as this new Enough Project video from the region makes clear.

There are five main obstacles plaguing current efforts.

First is the lack of capable and committed forces. Regional militaries have approximately 1,700 troops deployed in a densely forested area the size of Arizona that lacks roads and infrastructure. The Congolese army is planning to transfer its U.S.-trained battalion from LRA-affected areas to eastern Congo in order to combat the M23 rebellion. Meanwhile, Uganda’s commitment to ending the LRA appears likely to wane in the coming months. With the current force strength and the probable drawdown, how can the national militaries effectively search for LRA leader Joseph Kony and his senior leadership, and protect civilians?

The African Union envisions a Regional Task Force of 5,000 troops to fight the LRA and protect local communities. But the countries involved – Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, and the Central African Republic – appear unwilling to provide additional soldiers.

Second is the lack of real-time information about the LRA’s whereabouts. While allegations recently surfaced that Kony is in or near the Darfur region of Sudan, conflicting statements by Ugandan and U.S. officials suggest that they do not know where he is. The U.S. appears to be providing only a few aircraft for surveillance of the vast area in which the LRA operates. And without enough troops on the ground, it will be difficult to gather information critical to the capture of LRA commanders.

Third, the regional militaries lack transportation, such as helicopters, needed to rapidly follow up on reports about the LRA.

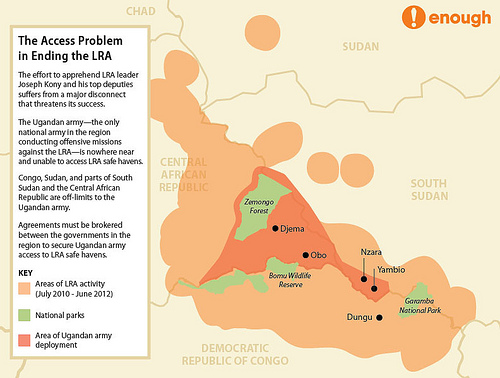

Fourth, there are large areas that have effectively become safe havens for the LRA. For more than nine months, Congo has been off-limits to the Ugandan army under orders from the Congolese government. We’ve seen the results of this: a spike of more than 90 reported LRA attacks in Congo since March 1, 2012. The Enough Project's on-the-ground research indicates that parts of CAR also remain off-limits to the Ugandan army. And Kony may have added another haven, if recent reports of LRA presence in Darfur are accurate.

Finally, efforts to encourage LRA commanders and fighters to leave the group require more resources and a clear strategy. Large areas remain where there are no FM radio stations broadcasting "come home" messages to LRA combatants and no places for them to surrender. The recent dissolution of Uganda's Amnesty Act, which in the past has allowed LRA fighters who renounce rebellion to walk free, and the ongoing trial of a mid-level LRA commander, Thomas Kwoyelo, are discouraging current combatants from escaping. And efforts to reach out to LRA commanders to encourage them to defect do not appear to be underway. These represent major lost opportunities.

More capable and committed troops in sufficient number are urgently needed. Highly trained special forces should carry out operations to arrest the top leaders, while other dedicated and skilled troops should protect civilians.

The Obama administration must knock on doors to secure troops. If the Ugandan and other armies are unable to provide them, the U.S. should reach out to South Africa or other African countries to get soldiers for the African Union force. A strategy for effectively protecting civilians and LRA abductees must be developed and implemented, and accountability for any human rights and other violations must be ensured.

Real-time intelligence and rapid response transport are critical. The administration needs to provide sufficient intelligence and transportation capabilities, and it should ask European and other countries to lend their support.

The U.S. must put its diplomatic weight behind securing access to all LRA-affected areas for the relevant troops. President Obama and his senior officials should engage the governments of Uganda, Congo, CAR, and Sudan toward this end.

The administration must also maximize opportunities for LRA combatants to return home. As confusion over the Amnesty Act continues, only the top three commanders wanted by the International Criminal Court should be prosecuted, and the Ugandan government should establish a truth-seeking initiative. Also required are greater efforts to communicate with LRA commanders and more resources for encouraging rank-and-file fighters to defect.

Like the ill-equipped pair of soldiers in CAR, the forces deployed to pursue the LRA are often unprepared and incapable. If they are to succeed, with the help of U.S. military advisers, then the above courses of action, along with support for reconstruction and economic development, are urgently needed. Only then does the international community have a real chance of ending this conflict and allowing communities that have been affected by the violence to rebuild and recover.