The Enough Project’s Justine Fleischner recently returned from a month-long trip to South Sudan and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where the regionally mediated peace process is underway. As part of Enough’s new interview series, Fleischner spoke with Greg Hittelman about what she saw.

In the nine months of South Sudan’s recent conflict, an estimated 1.7 million people have had to abandon their homes and communities. What is it like in the camps where some of these people sought refuge?

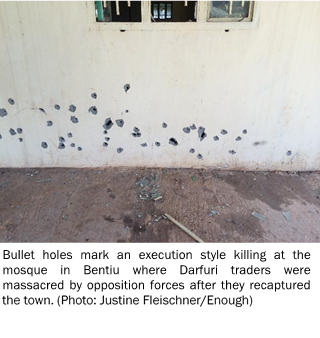

Fighting initially broke out in the capital city, Juba, on the night of December 15, 2013, and it quickly spread from the army barracks to residential areas. Terrified civilians sought refuge from the UN and cut through the barbed wire fences to escape the fighting on the streets and ethnic targeting by the security forces. The UN ultimately resolved to throw open their gates, saving countless lives and establishing a new precedent for the protection of civilians in response to a crisis situation. It also resulted in the impromptu relocation of tens of thousands of civilians in a matter of days from their homes to UN bases, not just in Juba, but in Bentiu, Bor, and Malakal as well. These sites are not refugee camps in the traditional sense and are called POC sites, which stands for protection of civilians. I visited two camps while I was there, the Juba Tongping site and the Bentiu POC site, where fighting is still ongoing.

In Juba, there were close to 27,000 people living in the camp I visited at the time, but most have now moved to a new site set up by the UN to provide better services to the 100,000 or so people that are seeking protection there. This number is expected to continue to rise with the onset of the dry season and the worst famine the world has seen in decades. While the conditions in the camp in Juba have dramatically improved, and a cholera outbreak has been contained, the situation is unsustainable. The longer the conflict continues, the deeper the divisions between communities in Juba.

In Bentiu, another camp I visited, over 45,000 people are currently seeking refuge, and the conditions are far worse than anything I have ever seen. Flooding and ongoing fighting have made the humanitarian response exceedingly difficult. More families arrive every day on foot seeking protection, food, and medical care. Flooding is a major issue and some families are living knee deep in water. While I was there in June, Médecins Sans Frontières released a statement that 3 children under 5 die every day in the Bentiu camp. The situation is expected to intensify over the coming months as famine sets in.

Tell us about the children living in these protection sites. Following South Sudan's independence, there was so much hope. And this was supposed to be the first generation in at least two decades not to grow up in the middle of a war.

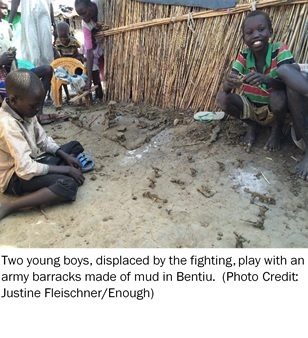

South Sudan is a young country and young men do most of the fighting. In the camps, women and children have been most hard hit, both by the breakdown of their communities and by the impact of violence. As I was walking through the camp, my translator pointed out a group of young boys playing in the mud. They had built an entire army barracks complete with toy soldiers, guns, and tanks out of the mud. One of the boys pointed his mud AK-47 at me and asked for his picture to be taken. My translator also insisted that he wanted to take me to see the primary school they had set up in the camp. Because the thatched structure the NGOs had set up was flooded and falling down, the children – dozens and dozens of them – were all sitting out in the hot sun watching two teachers write in faint chalk on a misshapen piece of black board the letters of the English alphabet. One young boy I knelt down next to, he could have been four or eight, was diligently copying the letters with his finger in the mud. My translator explained, these children are desperate to learn, and this war has stolen that from them. These are not conditions for children to learn in, but they were making every effort nonetheless.

South Sudan is a young country and young men do most of the fighting. In the camps, women and children have been most hard hit, both by the breakdown of their communities and by the impact of violence. As I was walking through the camp, my translator pointed out a group of young boys playing in the mud. They had built an entire army barracks complete with toy soldiers, guns, and tanks out of the mud. One of the boys pointed his mud AK-47 at me and asked for his picture to be taken. My translator also insisted that he wanted to take me to see the primary school they had set up in the camp. Because the thatched structure the NGOs had set up was flooded and falling down, the children – dozens and dozens of them – were all sitting out in the hot sun watching two teachers write in faint chalk on a misshapen piece of black board the letters of the English alphabet. One young boy I knelt down next to, he could have been four or eight, was diligently copying the letters with his finger in the mud. My translator explained, these children are desperate to learn, and this war has stolen that from them. These are not conditions for children to learn in, but they were making every effort nonetheless.

In the decades of war prior to South Sudan's independence, the use of child soldiers was prevalent. We are hearing reports this is happening once again.

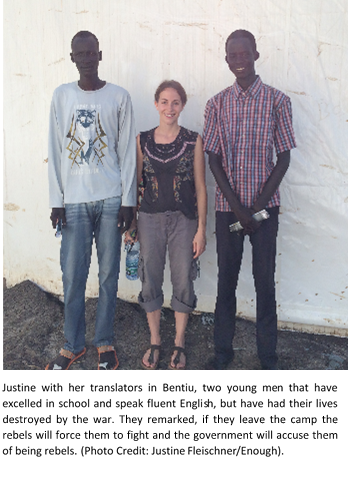

Yes. Both sides are using child soldiers and civilian militias that also include young boys. The UN reported that there are at least 9,000 child soldiers, but that number is difficult to confirm. While I was waiting to board the plane in Bentiu to fly back to Juba, my flight had been cancelled the day before because there was fighting around the airstrip, two government army trucks showed up with a few young boys in the back. One was armed with the South Sudan standard AK-47 and had a line of excess ammunition thrown over his shoulder. They jumped down and walked around close to the gate of the airstrip. Their uniforms were a size too large and their feet dry and cracked in the flip-flops they were wearing. I think the unspoken tragedy of this civil war is that yet another generation has been indoctrinated into violence and conflict, and the lingering trauma that comes with it.

What is driving so many people to seek protection? Is it to escape warfare, or is hunger the main thing?

South Sudan has been sliding towards famine for months now and was already suffering from food insecurity before the civil war broke out. Less than half of those targeted for humanitarian assistance have been reached, and that is mainly a result of insecurity and limited access to some incredibly remote areas. The short answer is both – but each family has made the difficult decision to seek refuge for their own reasons. One family I spoke with in Bentiu that had just arrived shared how they had been hiding in the bush for months unsure if they should risk the four or five day walk to try to reach the UN in Bentiu or not. They had young children with them, but their home had been burned, their cattle looted, and their crops destroyed. They finally made the decision to try to get to the UNMISS base in Bentiu seeking not only protection, but food and medical care for their children as well. The conditions they live in are absolutely appalling. This family in particular, which had just arrived, had not yet received adequate materials to build a shelter and had been flooded out in the middle of the night. It is difficult to describe how ferocious storms can be during the rainy season in Unity state.

And what’s the situation now in Juba?

In Juba, families are also faced with a complex set of factors on whether or not to move to the new site or try to reclaim their homes in Juba. While the government is adamant that security had been restored, most Nuer families I spoke with, and particularly young men, are terrified of what might happen to them at night at the hands of the security forces. It is true that some families have decided to return home, but many more have relocated to the new site in Juba. Many Nuer leave the POC site in the morning for work or school, and return in the evening before the gates close at night. This is how they have lived for months now, and while not ideal, they have made a home for themselves on the POC site under the protection of the UN peacekeepers. At the same time, many have lost their homes, businesses and farms. Their children have also been pulled out of school and the communities they grew up in. These communities have set up markets and relocated their businesses to the protection sites in order to carry on with life as close to normal as possible, but it’s not the life they want to lead. It’s not what independence promised them. The longer the war continues, the more divided communities will become. I think trust will be deeply difficult to restore in Juba.

So what are the prospects for an end to this war?

The mediation team has attempted to force a political settlement that would allow Kiir to stay on as President throughout the transition, but this has been rejected by the opposition and other groups at the negotiations. At the moment, neither side seems truly invested in peace. From our perspective at Enough, you have to change the cost-benefit analysis of the warring parties and create consequences for those responsible for human rights violations, mass atrocities, and obstructing humanitarian assistance. To best accomplish this, we would like to see a globally enforceable sanctions regime against designated individuals that have significant assets in bank accounts and properties in neighboring countries like Kenya and Uganda. The US and EU have already adopted limited sanctions designations, but these are not globally enforced. In order for action to be taken by the [United Nations] Security Council, regional countries will have to lobby for the support of Russia and China, two countries that would ultimately block any unilateral action by the United States. This is a regionally led peace process that requires the region take the lead on sanctions. A new 45 day deadline has now been set by the regional mediation team, but ideally action would be taken before then in order to build momentum towards a peace deal in advance of the deadline.

Are you saying that President Salva Kiir and the rebel opposition leader former Vice President Riek Machar, have the ability to make peace, but simply don't want to? How are they benefiting by continuing this conflict?

Granted they both have hardline constituencies and deep historical rivalries they are catering to, but of course they could choose to set aside these differences at any point and raise their voice for genuine peace and reconciliation. The truth is, like most post-colonial and post-conflict states that have long legacies of violence and oppression, both Kiir and Machar represent the pinnacle of elite interests of the ethnic communities and patronage networks they represent. There are complex historical and cultural dimensions to how patronage systems work in South Sudan, but there is also a simple truth to how oil wealth, development support, and land deals were stolen by these elites to serve their own self-interests. Both sides benefitted from corruption and they are now fighting, not just over political power, but access to economic windfalls that come with control over the government. The war is also not sustainable financially and companies like Exxon have already pulled out. The government is having trouble securing additional oil loans and groups like Global Witness have called for a moratorium on oil contracts since elites are selling off 30 years of future oil production – basically South Sudan’s future – in order to fight this war.

If the spoils of profit and power are largely what these elites are fighting over, then what does an eventual peace settlement look like?

The IGAD mediation team had presented a framework for what a peace settlement might look like to the parties for feedback, including civil society groups. There is broad agreement on what issues need to be dealt with during the transitional period – security sector reform, political reform, justice and accountability, reconciliation, the drafting of a new constitution, and preparation for national elections – but nearly no agreement on who should lead the transition. Many Nuer have said they cannot accept Kiir remaining in power for the duration of his term, let alone the transitional period, so it seems that is where the negotiations have reached an impasse. The position of the government of course, as one official put it, is that “the government of the day must be respected” and that regime change cannot be achieved through violence. The opposition has also said there cannot be a permanent ceasefire until there is a political settlement in place. This is something that the mediation team needs to work out through an inclusive process and requires creating leverage through targeted sanctions enforcement.

The IGAD mediation team had presented a framework for what a peace settlement might look like to the parties for feedback, including civil society groups. There is broad agreement on what issues need to be dealt with during the transitional period – security sector reform, political reform, justice and accountability, reconciliation, the drafting of a new constitution, and preparation for national elections – but nearly no agreement on who should lead the transition. Many Nuer have said they cannot accept Kiir remaining in power for the duration of his term, let alone the transitional period, so it seems that is where the negotiations have reached an impasse. The position of the government of course, as one official put it, is that “the government of the day must be respected” and that regime change cannot be achieved through violence. The opposition has also said there cannot be a permanent ceasefire until there is a political settlement in place. This is something that the mediation team needs to work out through an inclusive process and requires creating leverage through targeted sanctions enforcement.

Another key issue for the peace settlement is wealth sharing and economic management. In terms of improving economic transparency and accountability, steps should be taken now to identify and freeze stolen assets and empower diverse accountability measures, including civil society efforts. Some good examples exist from Sierra Leone and the Congo, where communities have made great progress in establishing local oversight over the use of natural resource wealth. Examples include social audits where local government officials disclose information on public revenues and spending, or the Publish What You Pay campaign, which requires companies share payments to host country governments. Sophisticated yet simple public oversight and accountability efforts will be essential towards improving economic transparency and tackling corruption and conflict over South Sudan's vast natural resource wealth.

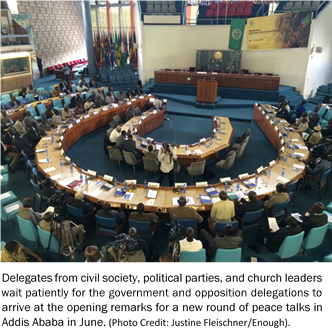

You were in Bentiu, one of the most conflict-affected areas in South Sudan, and then you were in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, where the peace talks are taking place. Talk about that disconnect, based on what you saw.

I do think there is a disconnect, partly because of practical and logistical challenges given South Sudan's size and limited infrastructure, but also because the government has clamped down on free speech and free press. Media outlets are not allowed to report the opposition's perspective and that limits space for public debate and the free flow of information about what is going on at the talks. The dichotomy between the plush hotels in Addis where delegates are staying and the conditions in the camps also speaks to the divide between the reality war-affected communities face every day and the lifestyles of the political elites.

Describe that divide.

The divide is apparent in the lack of urgency the parties have displayed at the peace talks, the buffet lunches, the luxury hotels where delegates stay, and the political jockeying that has taken precedence over the political transition. One civil society observer suggested the talks be moved back to South Sudan, to a flood-prone area where delegates could live on rations under similar conditions as their people, and that that would promptly result in serious progress in negotiations.

I also think the divide exists in the limitations of inclusivity at the talks. The selection of civil society delegates has been a challenging issue. There are limitations to how many people can sit at the table – how big the table should be – and it is a difficult to determine who has the right to speak on behalf of the people of South Sudan. I think the limitations of inclusivity in the form of direct participation at the talks have been recognized, but there is still a need to extend inclusivity to war-affected communities in South Sudan. At Enough, one way we have suggested overcoming this divide is by engaging in robust public opinion polling to allow these communities to weigh in on key issues related to the transition. Polling and data collection has been done under these complex conditions before, including on a limited basis in South Sudan, as well as Syria and Ukraine, for instance. Local firms, such as Opinions Oyee, have the technical know-how and cultural understanding to design the questions and the methodology. Statistically significant data could be influential at the talks to help galvanize civil society efforts to represent war-affected communities.

What are you working on now at the Enough Project, following on your research and recent experiences in South Sudan?

At the moment, I am wrapping up a report on the peace process and the political transition that looks at many of these issues in depth. I also spend a lot of my time meeting with policy makers and officials on ways to improve international engagement at the peace process and support a political settlement in South Sudan. Given all the competing crises unfolding around the world and sanctions fatigue, it is not easy work! I think there is a bright spot with South Sudan in that there is more or less great power alignment on the need for peace. Russia and China have no interest in an unstable South Sudan and if the region asks for sanctions, we hope the Security Council would respond.

You mention competing crises. What is it that makes the situation in South Sudan especially critical right now?

Famine, the worst man-made famine the world has seen in decades. There is also a lull in the violence now and if a peace deal is not reached by the time the rains stop and the road conditions improve, I'm afraid fighting will intensify. There are also larger geo-strategic interests, including oil investments. South Sudan's oil production has plummeted as the result of the war and investment projects have stalled, fueling illicit networks and instability in a region that suffers from chronic insecurity.

Would sanctions be a game changer? If so, what kind of sanctions would be needed?

I think they would be, particularly if they can effectively target those who are both politically influential and also have significant assets and property in neighboring countries that can be identified and frozen or seized. Maybe not top level officials, but those that are directly responsible for undermining negotiations or obstructing humanitarian assistance. South Sudanese elites have stolen well over $4 billion and that money is in places like Kenya, Uganda, South Africa, and Australia. Sanction designations could also be lifted once progress has been made in the negotiations, which was the case in Mali, where regional sanctions were lifted against the coup leader and his backers once the constitution was restored. Such a sophisticated use of targeted sanctions would ensure agreements that are made are kept. But, I should be clear that sanctions alone wouldn’t bring peace to South Sudan. It is about creating and using leverage as one tool at the mediators’ disposal alongside dedicated diplomatic engagement and a deep understanding of the root causes and drivers of the conflict.

What was the most moving experience you had during your recent time in South Sudan?

During a previous trip to Bentiu, I made friends with a basketball coach there named Sharnobi and we partnered together to form an NGO to help support his work coaching youth basketball in Unity state. When I was in South Sudan in November, right before the crisis broke out, I delivered huge bags of basketballs, socks, jerseys, and sneakers through a donation drive I had organized at a school for gifted inner-city youth in New York City. Sharnobi was caught up in the fighting in Bentiu and later arrested, actually by a rouge opposition commander, who demanded he fight since he is also an ethnic Nuer. He was released 17 days later but was in terrible health. I managed to get him flown to Juba and then on to Nairobi, so he was not in Bentiu when I visited last. He did however put me in touch with some friends there that guided me through the camp and provided translation. It's also much easier to talk to the community when people know who you are. My last day there, as I was waiting for my flight back to Juba, I was watching a group of young men loading up a massive World Food Program truck with boxes of USAID fortified cooking oil. Suddenly, my eyes were drawn to the filthy jersey one of the young men was wearing – a green Unity basketball jersey. He recognized me, but was so embarrassed by the condition he was in that he kind of smiled, softly greeted me in Nuer, and asked briefly about his coach before quickly going back to his work. To see this young man that had been so full of laughter and such a talented basketball player loading this mud caked truck in bare feet – well, it broke my heart.

What can average people in the U.S. and around the world do now to support peace and help the people of South Sudan?

Staying informed, staying engaged, reaching out to your representative in Congress, and raising awareness in your community are all important steps anybody can take. The more attention this crisis gets at home, the harder our government will work to solve it. At Enough, we have developed a community of dedicated individuals. I would encourage you to join us, learn more, and participate in our call for the U.S. government to support peace efforts and to sanction those undermining the peace process.