After a five year long trial, warlord-turned-president Charles Taylor was convicted yesterday of “aiding and abetting” a rebels notorious for their use of child soldiers and favor terror tactic, amputation, in the vicious 1991-2002 civil war in neighboring Sierra Leone in which an estimated 50,000 people died. The conviction is the first by an international tribunal of a former head of state since the Nuremberg trials of Nazi leaders, a development that was no doubt received with concern by the growing list of former leaders wanted for orchestrating atrocities.

Judges at the Special Court for Sierra Leone found Taylor guilty of 11 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, which could carry the equivalent of a life sentence when his punishment is given at the end of May. The crimes include murder, rape, slavery, and the use of child soldiers, which Taylor was found to have enabled by trafficking weapons to the rebels in exchange for blood diamonds. The prosecution did not allege that Taylor committed the crimes in person but through the Sierra Leonean rebel groups the Revolutionary United Front, or RUF, and the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council, or AFRC.

Unlike the other proceedings at the Special Court for Sierra Leone, which took place in the capital of Freetown, Taylor’s trial was held in The Hague on the grounds that it could stir tension and provoke violence in the region, where he still has a following. Taylor’s was the last case for the special tribunal, which was established in 2002. One indictee, AFRC leader Johnny Paul Koroma, is still at-large, but some reports indicate he may have died. The court is making arrangements in the event that he is apprehended after the court closes at the conclusion of Taylor’s expected appeals process. The special tribunal holds the distinction of being the first international court to issue a guilty verdict for the conscription of child soldiers in the 2007 trial of three AFRC leaders, which set an important precedent for the ICC case of Congolese former rebel leader Thomas Lubanga, who in March was convicted of recruiting child soldiers.

As Charles Taylor paves the way as the first former government leader convicted in a modern international court, here’s a list of the other wanted individuals who likely watched today’s verdict with keen interest—and they were joined by at least one standing president who isn’t even wanted (yet):

Laurent Gbagbo, former president of Ivory Coast: After a nearly yearlong standoff over the results of the 2010 presidential election that deteriorated into widespread ethnic violence, the disgraced former president was apprehended under a sealed ICC arrest warrant and transferred to The Hague. Gbagbo, who reportedly shares a prison compound with Taylor, is set to appear in court for his confirmation of charges hearing on June 18.

Omar al-Bashir, current president of Sudan: First wanted in 2009 for seven counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Darfur, the ICC’s chief prosecutor succeeded in adding three charges of genocide to Bashir’s list of alleged offenses in 2010. He evades arrest by surrounding himself with a coterie of devoted advisors, doing his best to keep the army close, and making a point of traveling to ICC non-member states, just to prove he can.

Jean-Pierre Bemba, former vice president of the Democratic Republic of Congo: Before he rose to the seat of vice president and later was a front-runner for president, Bemba allegedly commanded fighters with the Movement for the Liberation of Congo to commit atrocities in the Central African Republic as part of an effort to repulse a coup attempt threating then president of CAR, Ange-Félix Patassé. The ICC issued an arrest warrant under seal on May 23, 2008, and Bemba was arrested by Belgian police the next day. Bemba has been on trial since November 2010 for five counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Slobodan Milosevic and Muammar Qaddafi would have also made the list, but both died before justice—in the formal sense of the word, some might say—could be handed down.

While critics disparage the ICC and the special tribunals for their drawn out processes, challenges (in some cases) pinning direct responsibility on high-level leaders, and/or disproportionate focus on Africa, the list above is a testament to progress made over the past decade. It would be easy to argue that there are several current leaders worthy of the ICC’s attention, but for now, the only outstanding warrant for a head of state is for President Bashir—certainly a very unenviable distinction to hold.

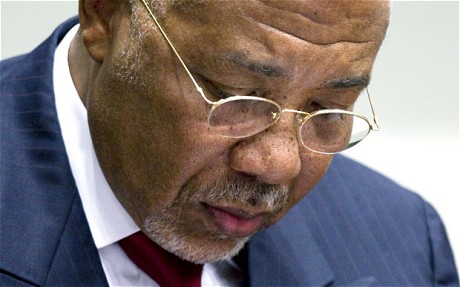

Photo: Charles Taylor at the reading of the court's verdict yesterday (AP)