In a recent post for Think Progress, guest blogger Lauren Jenkins raises some salient concerns about the provision of air defense capabilities to the Government of Southern Sudan, an idea that Congressman Don Payne (D-NJ) proposed during last week’s hearing on Sudan. Given that Enough endorsed this approach in a press release that same day, it’s worth taking a moment to address some of these concerns.

Providing air defense capabilities to the South Sudan government is neither an ideal response to the rising violence in Sudan, nor a step that should be undertaken rashly. But the chilling reports coming out of the Nuba Mountains suggest the wider potential for mass violence in the region and demand a consideration of all the options available to protect civilians from further harm, consistent with the international Responsibility to Protect doctrine, which is premised on the idea that the international community must act when a government abdicates its own responsibility to protect its citizens and commits atrocities.

Unfortunately, the options available are not good. Strengthening U.N. peacekeepers in the region sounds appealing, but the fact is that the Government of Sudan has been dropping bombs near U.N. bases in South Kordofan and some of the Egyptian peacekeepers in the region have been accused of siding with the Sudanese army and have lost the trust of local populations. Moreover, in response to mounting violence in Abyei, and to fighting between the SPLA and militias in South Sudan, the U.N. response has been to stay out of the way. A deal to get a robust Ethiopian peacekeeping force into Abyei is a welcome development, but it should be clear that U.N. peacekeepers have proven themselves unable to credibly protect the most vulnerable of Sudanese civilians at present.

What about a no-fly zone? Jenkins notes the controversy this proposal generated when it was endorsed by Hillary Clinton in 2007, but the more recent example is Libya, where the U.N. imposed a no-fly zone and authorized the much more significant military action currently underway. In Darfur, the problem with a no-fly zone is that it would have threatened humanitarian access to the millions of displaced persons in the region. Today in South Kordofan, humanitarian access has been almost completely blocked by the Sudanese Armed Forces, such as through the bombing of the airfield at Kauda, which would have been essential to getting aid into the region. But the fact is that even if a no-fly zone could help deter further bombing, there is little prospect for international authorization, especially with Russia and China ready to block any such action because of their perception that Western governments have taken a civilian protection mandate in Libya and used it to pursue regime change. The deadlock at the Security Council has not just taken a no-fly zone off the table, but also blocked additional measures that could be considered, such as an expanded arms embargo on the Sudanese government, to say nothing of direct military action.

Which brings us back to air defense. The concern that such capabilities could be used to target civilians is valid, which is why the provision of equipment needs to be accompanied by training, close monitoring, and be conditioned upon rigorous vetting of southern forces to make sure they have both the will and means to use these capacities responsibly. Given some of the alarming reports of SPLA violence in the South, it is hard to overstate the degree to which the United States would need to exercise control over this process.

Jenkins is especially correct to note Khartoum’s use of attack aircraft painted to look like U.N. flights in Darfur and the potential for similar tactics that could put humanitarians at risk from southern missiles. There is no doubt that the training and equipping of the southern army would need to be accompanied by the development of rigorous systems to distinguish U.N. flights from military bombers – systems that would have to rely upon more than just what color a plane is painted.

There is also the possibility of doing nothing, given the possibility for any action to do more harm than good. But let’s be clear about the possible consequences of this approach. The South, which has been asking for air defense capabilities for years, has been covertly rearming in preparation for potential war all this while. There is no doubt they will use the benefits of sovereignty to expand their arsenal, and the alternative to U.S. support is likely to involve much cheaper and more easily trafficked weapons including man-portable air defense systems, which can easily be used for purposes other than those intended and would likely be delivered without conditions. This would have all of the alarming negative consequences and none of the supervision that a more responsible U.S.-assisted program would entail.

It is important to clarify the objectives, limitations, and consequences of U.S. support for South Sudan air defense. The likelihood of U.S.-provided arms being used to down Antonov bombers in Sudan in the next couple of months is zero. But the United States can take tangible steps to begin training southern forces in the use of these systems, vetting units to participate in the program, and shaping the contours of a policy that would be a less worse way to try to protect civilians in the region than the alternatives.

Putting this process into place will take time. But unlike direct military action or a no-fly zone, which are effectively empty threats, credible planning for long-term air defense support will have an immediate influence on the calculations of Sudan’s ruling party whose systematic use of aerial bombardment of civilian populations remains premised upon a solely rhetorical international response. In this regard, it should be only one component of a more comprehensive effort to use both incentives and pressures, unilateral and multilateral, to press the Government of Sudan to abide by its previous commitments and use peaceful means to navigate the future relationship both with its new southern neighbor as well as with its own people.

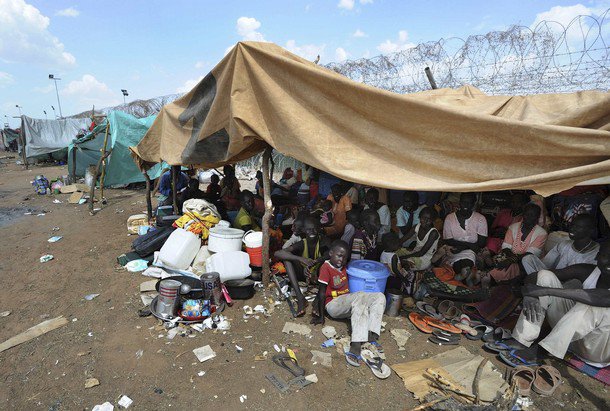

Photo: Displaced people gather outside of the UNMIS compound in Kadugli (UNMIS)