Enough experts break down the possible outcomes of the upcoming referendum vote in Sudan.

Read the Activist Brief (PDF) >>

All signs indicate that Sudan, Africa’s largest state, will very soon split in two—either peacefully or violently. In a self-determination referendum scheduled for January 2011, the people of southern Sudan are widely expected to vote for separation from their northern neighbors. Yet with the security situation in southern Sudan deteriorating, next month’s national election set to be deeply flawed, and several crucial elements of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, or CPA, still unimplemented, the referendum and its outcome are by no means guaranteed. As a guarantor of the CPA, the United States must work multilaterally on several fronts to support the peaceful expression of the will of the people of southern Sudan and prevent a return to conflict.

The two parties to the CPA—the National Congress Party, or NCP, and the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Army/Movement, or SPLA/M—have a laundry list of difficult tasks to accomplish before the 2011 referendum. Next month’s elections will occur against a backdrop of intense political jockeying for position and rising tensions between the two parties. And while the Sudanese government has agreed to allow some external monitoring of the election, few Sudanese expect a credible process under the repressive security environment that persists throughout the country, particularly in the North.

The NCP and the SPLM must reach agreement on both outstanding CPA provisions and on post-referendum arrangements to avoid a return to war. Moreover, the international community must work to halt the downward spiral of intercommunal violence in southern Sudan—a situation that threatens the referendum altogether.

Unfortunately, the sustained multilateral pressure and unity of international purpose that yielded the CPA has not accompanied its implementation. In the absence of coordinated efforts by the international community, the United States remains the de facto external lead player on Sudan. However, U.S. efforts to date have assumed a level of good faith in the parties—particularly the ruling NCP—that simply does not exist. The NCP and SPLM reached agreement on areas of mutual interest with very little external facilitation. But with only nine months left before the referendum, there are major issues of disagreement that require international mediation if a return to conflict is to be averted. It is in these areas that the United States is expected to lead international efforts to facilitate compromises and to coordinate the development of multilateral pressures and incentives necessary to leverage such compromises.

The Obama administration must work urgently to support the parties in defining a clear framework for two distinct sets of negotiations: the resolution of outstanding CPA provisions and the initial discussion of post-referendum arrangements. For talks to succeed, the United States must work multilaterally to put meaningful pressure on the NCP and SPLM to find common ground on the CPA and the contentious issues that will accompany an independent southern Sudan. This approach is consistent with the Sudan policy unveiled by the Obama administration in October 2009, but the policy has not yet been implemented.

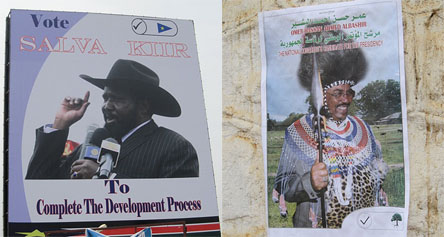

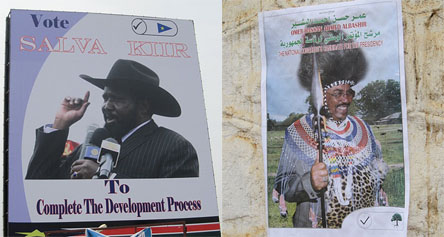

Sudanese campaign posters for President's Salva Kiir (Southern Sudan) and Omar Bashir (Sudan). Photos by Maggie Fick / Enough

A ticking time bomb

Last year, Enough warned that the international community was at risk of sleepwalking through national elections and the run-up to the referendum.[1] Today, more international actors are clearly concerned about the potential return to conflict between North and South. Despite this increased attention, however, the trend lines in Sudan remain decidedly negative. Violence is rife in the South and in Darfur, state-sponsored political repression remains the norm in the North, implementation of key CPA provisions is effectively stalled, and a number of potentially explosive post-referendum issues remain unresolved. The recent agreement between the government of Sudan and the Justice and Equality Movement, or JEM, in Darfur, which appears to be unraveling quickly, is a good example of the substantial risks carried by poorly executed negotiations at this juncture.

1. Southern Sudan: Spiraling insecurity threatens the referendum

More than 2,500 people were killed and 350,000 displaced last year in southern Sudan.[2] Much of this violence is undoubtedly linked to historic tensions between southern groups over cattle and other resources, coupled with growing discontent over the lack of “peace dividends” received by the majority rural population across the South.[3] However, there is likely another historic trend at play. Throughout its two decades in power, the National Congress Party regime in Khartoum has frequently armed local proxies to wage war on its behalf and sow instability in Sudan’s marginalized peripheral areas.

Today, some reports indicate that Khartoum has provided arms to militias to attack civilians.[4] With this demonstrated track record of proxy warfare and now mounting anecdotal evidence, the perception among Southern leadership and some local populations is that Khartoum is the hidden hand behind recent violence. This perception is one that the Obama administration, and the international community more broadly, must take very seriously while still holding the GoSS accountable for its own shortcomings in the security sector.

Accusations by GoSS officials have stoked tensions between Juba and Khartoum and exacerbated barely below the surface rifts between communities in southern Sudan. The NCP’s hand has been strengthened by widespread perceptions that the GoSS has been incapable of extending authority throughout a vast, largely remote, and often inaccessible territory. Khartoum’s response to the intertribal violence has also helped to fuel mistrust between the parties and fostered the notion in some certain diplomatic circles that Sudan and its neighbors would be “better off” if Sudan remained united, implying that the South is incapable of “governing itself.”[5]

If 2009 was bad, 2010 may well be worse. Last August, a senior U.N. official characterized the situation in southern Sudan as a “humanitarian perfect storm.”[6] Deadly clashes have already occurred this year in four of the South’s 10 states and the threat of Lord’s Resistance Army, or LRA, rebels persists, particularly near the South’s borders with Darfur, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Central African Republic.

April’s elections could aggravate this already tense situation. A core element of the GoSS’s pre-elections security strategy is a military campaign to disarm civilians in areas with the greatest potential for election-related violence.[7] Despite efforts to improve upon past disarmament disasters, current campaigns in Central Equatoria, Jonglei, and Lakes state have directly led to violence and casualties among civilians and the army.[8] [9] The SPLA is charged by state-level security committees with carrying out disarmament, which the GoSS publicly described as “voluntary” and only coercive if civilians refuse to hand over their weapons to the SPLA.[10] However, according to a senior official with the U.N. peacekeeping mission in Sudan, or UNMIS, rank-and-file soldiers are not trained in conducting voluntary campaigns, often leading soldiers to revert to coercive tactics.[11]

Communities have armed themselves—or are still holding onto the weapons they held during the war—in large part because they fear attacks by neighboring communities. Disarmament alone will not assuage these fears. Unless the SPLA and the GoSS devise a strategy for guaranteeing the security of disarmed communities and put greater efforts into community-level reconciliation, many communities will continue to arm themselves.

Indeed, the problems that come with a heavily-armed civilian population cannot be addressed through disarmament alone and must instead be part of broader security sector reform efforts with significant buy-in and support from donors and the international community. As one UNMIS official told Enough, “It takes a generation to get security sector reform right.”[12] With this realization in mind, it would be wise for the international community—particularly the United States and other actors already in the lead on funding security sector reform programs—to do the hard thinking now on how best to support these efforts beginning immediately after the referendum and beyond.

Given the likelihood of insecurity surrounding both the elections and the referendum, the international community also needs to work with the GoSS to anticipate and respond appropriately to outbreaks of violence in the coming months. However, security sector reform is challenging even in an environment of peace and stability and with genuine political will. It may prove almost impossible over the next year as all sides position themselves for a potential return to war.

[pagebreak]2. Northern Sudan: State-sponsored violence and intimidation

The repressive political climate in North Sudan is not conducive to even marginally credible elections. The majority of northern Sudanese do not live with basic freedoms such as the ability to participate freely in opposition politics, freedom of assembly, or access to a free media. In the recent protracted negotiations with the SPLM over a package of CPA-related laws, the NCP resolutely refused to reform the National Security Law that enables the government nearly unchecked powers to detain and intimidate its people. With little outcry from international diplomats, some of the truly transformative cornerstones of the CPA were simply abandoned.

The voter registration period in late 2009 was marked by Khartoum government’s use of its security forces to harass, abuse, and detain those attempting to challenge the ruling NCP.[13] In early December, Khartoum’s security forces used tear gas against peaceful opposition protestors organized by the SPLM’s northern sector in Khartoum; several senior SPLM leaders, including the SPLM’s presidential candidate Yassir Arman, were beaten and detained.

Despite a recent—and increasingly—fragile framework peace agreement between the government and the largest rebel group in Darfur, the crisis there is far from over. Nearly 3 million civilians have been driven from their homes and warehoused in sprawling camps for refugees and displaced persons. A government offensive has killed hundreds and displaced tens of thousands in recent weeks. And while the Sudanese government controls major towns, other armed groups—government-aligned militia, government-backed Chadian rebels, and Darfur’s fractured rebellion—have loose control over large tracts of territory and harass and terrorize civilians and aid workers with impunity. There is also widespread evidence that elements of the LRA, have found safe harbor in areas of Darfur controlled by government forces.

3. CPA implementation: The great unraveling

The CPA offered the promise of democratic transformation, but a true change in the political dispensation that lies at the root of so much conflict in Sudan requires the NCP and the SPLM to embrace democratic principles. Sadly, the parties have generally not chosen to pursue this path. The recent deal reached between the parties on the number of national parliamentary seats allocated to the SPLM ended a long deadlock related to a dispute over the 2008 census results, but it is arguably an example of how the CPA has been treated—and in some cases, manipulated—by each side. While the NCP has often attempted to avoid implementing the spirit and letter of the CPA, the SPLM has sought short-term advantage and political gain or mere survival, sometimes pursuing strategies that come at a cost to its image and its already shaky democratic credentials.

Despite this trend, it is important to note that the details of the late-breaking deal on parliamentary representation (which will impact the elections) are still being worked out. The SPLM is showing promising signs of supporting a more equitable process to accurately represent the degree of support opposition parties’ hold in each of the 10 southern states. Should the SPLM follow through on its recent statements regarding parliamentary representation of opposition forces in the South, this would be a step in the right direction, although it does not change the North-South deal-making dynamic that often continues to block the more transformative elements of CPA implementation.

Among a long list of CPA provisions that remain unimplemented, several pose the threat of sparking a return to conflict and should be prioritized:

Demarcation of the North-South border: “To me, the border demarcation is more important than the elections,” a leading GoSS official remarked to Enough. [14] The North-South Technical Ad Hoc Border Committee has been unable to reach agreement in its final report to the Government of National Unity, or GoNU, presidency on the 2,100-kilometer North-South border due to "procedural and substantive disagreements" between the NCP and SPLM over five particular sections of the border.[15] However, following NCP-SPLM discussions in mid-February, the two parties agreed to immediately begin demarcating the agreed-upon sections of the border and requested that the committee submit a report to the presidency within two months detailing the five disputed sections of the border. UNMIS has been denied access to several contested areas along the border—notably the Heglig oil fields that (following the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s July 2009 Abyei ruling) lie outside of the Abyei region (the Sudanese Armed Forces interprets this new status to mean that the Heglig –Kharasana area is outside the ceasefire zone specified in the CPA).[16] If key border areas remain undemarcated, they will be obvious wellsprings for renewed violence.

Residency requirements for the Abyei referendum: The contested region of Abyei remains a major flashpoint where the parties will resort to conflict in order to demonstrate their commitment to their local constituencies—for the SPLM, the Ngok Dinka native to Abyei, and for the NCP, the Misseriya nomads, who seasonally migrate through the region.[17] In Abyei today, 20,000 residents remain displaced from the May 2008 fighting between SAF and SPLA forces. Demarcation of the Abyei boundaries has been plagued by security issues and SPLM claims of the NCP intimidating the joint border demarcation committee.

Constitution of the Southern Referendum Commission and other preparations: Although the government signed the Southern Referendum Law into law in early February, the Referendum Commission has not yet been formed. For that to happen, the National Assembly will need to be called back from its pre-elections recess in order to approve the members of the Referendum Commission nominated by the presidency. Given the precedent of extreme delays in the two other major CPA processes to date—the census and the elections—it is likely that the referendum preparations could be plagued by similar roadblocks. The referendum is a “redline” for the SPLM and the people of southern Sudan; any delay in the holding of the referendum could easily spark a return to North-South conflict.

Post-referendum issues

A recent Chatham House report described 12 distinct post-referendum issues that the parties will likely face after the January 2011 referendum.[18] Given the contentious nature of questions surrounding future relations between the North and South in the likely event of separation, some of these issues in particular should qualify as “must-discuss” topics prior to the referendum. These issues include the wealth-sharing aspects of post-referendum arrangements, which include division of and access to Sudan’s oil and water resources. Division of assets and liabilities (including Sudan’s sizeable foreign debt, much of it incurred during the North-South war) is another negotiation process that would benefit from initial discussion between the parties prior to the referendum, as is the issue of migratory rights for pastoralist populations along the North-South borders. While no single issue facing North and South is unresolvable, the sheer volume of issues on the table, the high stakes involved, and the rapid timetable for negotiations make for an explosive combination.

[pagebreak]Calculations of the parties

Neither the NCP nor SPLM have an interest in returning to all-out war. Unfortunately, the main factor working against an outright return to North-South conflict is also the central reason why the CPA’s project of “democratic transformation” has failed: Both parties represent the ruling elites of North and South, and neither side wishes to give up their respectively precarious positions. An accommodation between elites in Khartoum and Juba could be in the offing, but both sides are understandably reluctant to accept potentially painful compromises on their overarching objectives: access to southern oil wealth for the NCP, and sustainable southern independence for the SPLM.

1. National Congress Party

At the fifth anniversary celebration of the CPA in January, President Bashir announced that his government would be the “first to recognize an independent southern Sudan.”[19] One interpretation of this statement is that the NCP would be willing to “let the South go” as long as its fundamental interests in the territory were upheld. The NCP’s interests are several fold: first, to maintain the party’s hold on power; second, to maintain significant control over oil resources in the South; and third, to emerge from international isolation without actually making meaningful concessions on either power sharing or accountability. If Khartoum and Juba can work out a mutually beneficial wealth-sharing arrangement—one that enables Khartoum to continue to reap the benefits of the South’s resources even after its independence—then war could be avoidable. In this scenario, the NCP would need to maneuver into an arrangement in which the SPLM has no choice but to concede some of its wealth to the North; should this move succeed, the NCP may view overt tampering with the referendum as unnecessary.

The NCP is well aware that construction of a pipeline to take southern oil reserves to a port other than Port Sudan is years—and billions of dollars—away. Therefore, the SPLM will have no choice but to engage in horse trading with the NCP over usage rights. This scenario illustrates the NCP’s cost-benefit calculations in its dealings with the SPLM on numerous post-referendum issues. If it can extract exactly what it wishes from its weaker southern partner, the NCP will most likely avoid war. However, the regime has been purchasing more and more sophisticated weaponry in preparation for the opposite scenario.

President Bashir has weathered the initial storm that followed the International Criminal Court arrest warrant in 2009—although the charges still represent an existential threat to his rule—and now appears guaranteed to win a flawed national election next month. In theory, the April elections will not re-legitimize Bashir despite the fact that he will almost certainly be elected in a multiparty contest for the first time since he took power by coup two decades ago. In practice, however, the elections will certainly give African and Arab nations who are already not wholly (or even mildly) opposed to Bashir’s leadership further reason to support Bashir as the legitimate, elected leader of Sudan.

The elections will also influence the way some Western nations view Bashir and his regime. The international community has invested significantly in the elections and their credibility—including $95 million in electoral assistance from the United States. Many donors view Sudanese elections less as a democratic exercise and more as a “trial run” for the referendum. Donors have been abundantly willing to overlook fraud and vote rigging simply to move on to what they consider the main event. Moreover, the NCP is well aware of the pressures and motivations of donors, as well as their long track record of recognizing the results of patently terrible elections. The once-lofty aspiration of a democratic Sudan as encapsulated in the CPA has been sullenly reduced to an expensive box-checking exercise.

Khartoum is better positioned to face the challenges present in the CPA’s waning interim period than the SPLM. From this position of strength, the NCP can confidently drive the agenda of the negotiations and resolutely refuse to compromise on anything—from reform of the National Security law to residency requirements for the Abyei and southern referenda—that will reduce its position.

2. Sudan People’s Liberation Movement

In his own speech at the recent CPA celebration, South Sudan President Salva Kiir made an important and telling point about the nature of the agreement that ended 23 years of war between Sudan’s North and South:

…[T]he CPA represents a landmark in Sudan’s political history since it put an end to war, created conditions and established ground rules for restructuring the Sudanese state politically, economically, administratively and culturally…[The]CPA is, essentially, a deal to find a middle ground between parties and it provides a spring board to realize our vision of New Sudan through democratic means. I equally believed that if CPA is realized fully in letter and spirit, it provides the last chance for Sudan’s unity. [Emphasis from original text.] [20]

That southern leaders have largely abandoned any hope for unity is left unsaid. Salva’s decision not to run for the national presidency is as clear an indication as any that the SPLM is focused on secession. The SPLM is now left to maintain its tenuous partnership with the NCP while challenging for national elections, addressing ongoing insecurity in the South, preparing for an independence vote, engaging in wide-ranging and complex negotiations, and continuing to struggle with the basics of administration and governance. This would be a tall order for even the strongest political unit. The SPLM, however, is undergoing a period of inner turmoil in the run-up to the elections. Not only is the SPLM aware of the popular discontent (particularly among minority southern tribes), with its leadership, but it is being forced to address challengers within the party.

The electoral process is putting a great deal of stress on the SPLM, evidenced by the political drama surrounding the party’s candidate nomination process and the subsequent proliferation of “independent candidates”—former SPLM members who opted to abandon the party after being rejected as SPLM candidates. If the SPLM chooses to use this contentious period as a learning experience—and makes efforts to re-engage with members of its wounded political leadership—the process could strengthen the party and better prepare it for the challenges ahead, particularly following the referendum.

Although there is no doubt that the SPLM’s top priority is ensuring a credible referendum takes place in January 2011, the party will be tied up in the electoral process through April. Many of the senior GoSS leaders—notably the Ministers of Regional Cooperation and SPLA Affairs—are running for parliamentary positions in their home constituencies. Other government officials are assisting the SPLM candidate for the national presidency, Yassir Arman, with his campaign. It is worrisome that the most competent SPLM politicians are currently not able to prepare the party for the crucial negotiations with the NCP that must occur between the elections and the referendum.

Because the SPLM has been so heavily focused on the independence option, it has become increasingly disinterested in pushing the NCP to make important reforms whether in terms of security laws or other basic freedoms in Sudan. This has been a considerable strategic mistake for the SPLM. By focusing only on southern parochial interests, the SPLM has largely lost its ability to find common cause with northern opposition groups. It was this more unified approach between northern opposition groups and the SPLM that was able to exert more decisive negotiating pressure on the NCP, and was able to garner important international support. Equally important, by looking increasingly unconcerned about such basic freedom in Sudan, the SPLM calls into question its own democratic credentials. Even while independence remains the final goal for the SPLM, this goal can be much more effectively advanced in concert with northern opposition groups rather than in isolation.

Once the elections are behind them, the calculations of the SPLM are clear: independence or war. While the preferred outcome for the SPLM would be a credible, peaceful referendum followed by an internationally recognized secession, a unilateral declaration of independence is not out of the question should the SPLM determine that the referendum has been partially or fully subverted by the NCP. The “red line” of the referendum for the SPLM means that any delays or major difficulties associated with the conduct of the referendum could provoke the Juba leadership to take steps toward another North-South war.

The SPLM is not yet able negotiate on equal terrain and with comparable acumen to the NCP. The party faces an uphill battle which will not end after the referendum or at the conclusion of the interim period. As the South’s ruling party continues to look northward and to prioritize the threats posed by its CPA partner, it risks ignoring mounting challenges within its territory that seem poised to heighten both in the run-up to and following the referendum.

[pagebreak]The way forward: Forging a framework and building the leverage for talks

There is no common strategy among the CPA guarantors and little coordination between actors—such as the Obama administration and the African Union Peace and Security Council, among others—that should be uniformly supporting the parties in defining a clear framework for two distinct sets of negotiations: the resolution of outstanding CPA provisions and the initial discussion of post-referendum arrangements. Neither of these two processes can be initiated prior to the elections, but the international community should use the run-up to the April polls to help the parties set up the frameworks, build the leverage, and establish the security environment necessary for these processes to succeed.[21] Instead, there seems to be little in the way of a common position among key actors in the international community, and this lack of a well-coordinated and clear policy line toward Sudan will only make conflict prevention more difficult.

1. The framework

The United States must assist the Sudanese parties in defining a framework for both sets of negotiations and then supporting this framework through a coordinated, consistent, and well-resourced international effort.[22] The Obama administration should immediately begin harnessing qualified personnel resources for the special envoy’s team and prepare to deploy them to Khartoum and Juba in order to assist in the preparations for these critical negotiations. The barebones U.S. diplomatic presence in Sudan at present is a more telling indicator of the Obama administration’s attention to Sudan than its soaring rhetoric.

The United States must continue to be the de facto leader of international efforts on Sudan in 2010 and likely beyond. This does not mean, however, that the United States should go it alone. While focusing U.S. attention on several high-priority issues will enable progress, it must be complemented by coordination with other international actors who have a comparative advantage in advising the Sudanese parties on certain aspects of the preliminary post-referendum arrangements.

The United States should therefore coordinate its support with the other CPA guarantors, with the United Nations and African Union, and with other countries with significant interests in the future stability of Sudan, namely China, Egypt, and other Arab nations such as Qatar. The need to avoid a disjointed process is paramount, given the limited resources and capacities of the parties and the timeline for these negotiations. A logical place to begin building greater policy coherence on Sudan would be at a U.S.-European Union foreign ministerial-level summit on Sudan.

No matter what framework is adopted, the parties must lay the groundwork for 2011 to ease fears that the referendum vote will result in “zero-sum” outcomes. This year’s negotiations can establish ground rules and preliminary understanding between the two parties on the clear hot-button issues that could inflame tensions immediately following the referendum. By providing support now to the parties in discussing the likely post-referendum realities, the international community could take an important first step toward post-referendum support to southern Sudan and preserving peace after the important vote.

2. The leverage

As a top UNMIS official noted, the ability of the parties to reach and carry out the referendum peacefully will depend heavily on international pressure on Khartoum.[23] Moreover, and per the CPA, southern Sudan has an internationally recognized right to secede should its citizens vote for separation in the referendum. This right must be upheld by the CPA’s guarantors. It is imperative that the CPA’s guarantors and other international actors engaged in Sudan communicate to the NCP in no uncertain terms that there is no alternative to the referendum being held on time and in an environment in which the poll can be credible. Relative international diffidence in the face of repeated NCP provocations may also embolden the party to engage in dangerous adventurism as the referendum approaches, including the seizure of disputed territories.

Implementation of the administration’s benchmarks-based policy is the best way for the United States to demonstrate its commitment to preventing a return to war and promoting sustainable peace in Sudan. Consistent application of conditional pressures and incentives on the NCP and the SPLM based on the two parties’ behavior in the remainder of the CPA interim period will support these objectives. Given that the NCP has engaged in a renewed offensive in Darfur, given safe harbor to the LRA, and utterly failed to hold anyone accountable for war crimes or crimes against humanity, many observers are now rightly questioning whether the administration’s benchmarks approach will be rigorously applied.[24]

The United States should also call for the expansion of the mandate of the U.N. Panel of Experts in Sudan to investigate the ongoing violence in southern Sudan and reports of an influx of small arms and heavy munitions into the South. The Obama administration must continue to pressure the NCP to reform the abusive National Security Law, as credible referenda and elections cannot take place unless Khartoum’s National Security Service’s broad powers throughout the country are curbed.

3. Security

When the UNMIS mandate comes up for renewal at the U.N. Security Council in April, the United States must call forcefully for a strengthened civilian protection mandate, drawing upon the recommendations recently made by operational humanitarian agencies working in southern Sudan.[25] The new mandate should emphasize preventive action, such as predicting flashpoints, and utilize active strategies such as temporary operating bases and long-range patrols. UNMIS can and should take far more forward leaning steps to operationalize its existing civilian protection mandate, but this will require the allocation of more resources and explicit directives and guidelines from New York. The U.S Permanent Representative on the Security Council, Ambassador Susan Rice, is well poised to work with other member states to adjust the mandate, and she should receive the full backing of the Obama administration in her efforts.

Conclusion

Although preparation now for both sets of negotiations is essential, it is up to the Sudanese parties to push these processes forward after the elections. Based on the history of NCP-SPLM negotiations before and after the signing of the CPA in 2005, it is likely that agreement on outstanding CPA provisions and initial discussions on post-referendum arrangements will occur at the eleventh hour. The role of the international community is to reduce the likelihood that these discussions end up occurring in such a politically charged environment that consensus between the parties becomes impossible. Sudanese presidential adviser Ghazi Salah Al-Deen Al-Attabani recently said that failure by the Sudanese parties to address post-referendum issues such as North-South border demarcation before the referendum occurs will be a “recipe for war.”[26] It is clear that the parties are cognizant of the need to begin these discussions prior to the referendum. The international community should support these efforts or begin preparing for the next of Sudan’s catastrophic civil wars.

Read the Activist Brief (PDF) >>

[1] See Gerard Prunier and Maggie Fick, “Sudan the Countdown” (Washington: Enough Project, 2009), available at www.enoughproject.org/files/publications/sudan_countdown.pdf.

[2] U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “Humanitarian Update Southern Sudan,” February 17, 2010, available at http://ochaonline.un.org/Default.aspx?alias=ochaonline.un.org/sudan.

[3] See International Crisis Group, “Jonglei’s Tribal Conflicts: Countering Insecurity in South Sudan” (2009), available at http://www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?id=6452.

[4] Human Security Baseline Assessment, “Supply and demand: Arms flows and holdings in Sudan,” Sudan Issue Brief. 15, December 2009, available at http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/pdfs/HSBA-SIB-15-arms-flows-and-holdings-in-Sudan.pdf.

[5] See Colin Thomas-Jensen, “Javier Solana’s Foot in Mouth Problem,” Enough Said, September 3, 2009, available at https://enoughproject.org/blogs/javier-solana%E2%80%99s-foot-mouth-problem.

[6] Lise Grande, UNMIS Deputy Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Southern Sudan, Opening remarks at African Press Organization press conference, August 12, 2009, available at http://appablog.wordpress.com/2009/08/12/press-conference-by-lise-grande-un-deputy-resident-and-humanitarian-coordinator-for-southern-sudan/

[7] Disarmament campaigns conducted throughout the South between 2006 to 2008 have been extensively analyzed and documented by the Small Arms Survey, most recently in a January 2009 paper by Adam O’Brien, “Shots in the Dark: The 2008 South Sudan Civilian Disarmament Campaign” Working Paper no. 16 (Small Arms Survey, 2009), available at www.smallarmssurvey.org/files/portal/spotlight/sudan/Sudan_pdf/SWP-16-South-Sudan-Civilian-Disarmament-Campaign.pdf; The GoSS Ministry of the Interior has directed the Southern Sudan Police Service, or SSPS, to take the lead on elections security; UNMIS police units are training SSPS and donor governments, notably the United States and the United Kingdom, are aiding in coordination and planning for police deployments throughout the South during the elections. According to the SPLA spokesperson, “The SPLA will release the forces needed to support the Police. The Police will then train them on the best ways to support and command them throughout the election period… the police senior officer[s] will be the ones to command the SPLA supporting forces during the elections.” Enough email correspondence with SPLA Spokesperson Major General Kuol Deim Kuol, January 28, 2010.

[8] Disarmament is currently underway in the States of Lakes, Jonglei, Central Equatoria, Warrap, Upper Nile, Unity, and Northern Bahr El Ghazal. According to a senior SPLA official, although the SPLA has been ordered to disarm the civilian population in all 10 states of southern Sudan no later than the end of June 2010, disarmament has not started in the States of Western Bahr El Ghazal, Western Equatoria ,and East Equatoria “because of the LRA atrocities in those States and [because] the tribes in neighboring countries of Kenya and Uganda are armed and raid the Sudanese communities.” The GoSS view is that “[disarmament in these three states] requires joint political decision by the GOSS and leaderships of those countries.”Enough email correspondence, senior SPLA official, January 28, 2010.

[9] U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “Situation Analysis of Akot Insecurity: Rumbek East County, Lakes State, 5-6 January 2010,” On file with Enough.

[10] Ideally, the South Sudan Police Service, or SSPS, would take the lead on civilian disarmament. However, in southern Sudan, the low capacity and resources of the police necessitate the use of SPLA forces in civilian disarmament. This is yet another reason why “voluntary” disarmament has quickly turned coercive and violent in the various campaigns in the South since 2006. Given that there are an estimated 14,000 police officers, with some sources indicating that no more than 9000 are effective, it is not surprising that the SSPS is overwhelmed in its attempt to address both pre-elections security and civilian disarmament, in addition to routine policing functions. Enough email correspondence with Juba-based security consultant, January 2010.

[11] Interview with senior UNMIS official, Juba, December 2009.

[12] Interview with UNMIS official, Juba, December 2009.

[13] See Human Rights Watch, “Sudan: Abuses Undermining Impending Elections” (2010), available at http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/01/24/sudan-abuses-undermine-impending-elections

[14] Interview with GoSS official, Juba, January 2010

[15]Report of the Secretary General on the United Nations Mission in Sudan (January 2010), available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2010/31

[16] Interview with UNMIS official, Juba, January 2010.

[17] See Colin Thomas-Jensen and Maggie Fick, “Abyei: Sudan’s Next Test” (Washington: Enough Project, 2009), available at https://enoughproject.org/publications/abyei-sudans-next-test; See also Roger Winter and John Prendergast, “Abyei: Sudan’s ‘Kashmir’” (Washington: Enough Project, 2008), available at https://enoughproject.org/publications/abyei-sudan%e2%80%99s-%e2%80%9ckashmir%e2%80%9d.

[18] See Edward Thomas, “Decisions and Deadlines: A Critical Year for Sudan” (London: Chatham House, 2010).

[19] Reuters, “Sudan’s Bashir says would help an independent south,” January 19, 2010, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE60I2P320100119?feedType=RSS&feedName=everything&virtualBrandChannel=11563 (last accessed March 2, 2010).

[20] Speech of H.E. Gen. Salva Kiir Mayardit, First Vice President of the Republic and President of GoSS, January 9, 2010. On file with Enough.

[21] As a recent USIP report noted, “There is little time to waste in defining the negotiation process and roles. With nationwide elections scheduled for April, there is a brief window for defining the process and roles before negotiations are likely to begin in earnest.” Jon Temin, “Negotiation Sudan’s Post-Referendum Arrangements,” USIP Peace Brief 6, January 22, 2010.

[22] The Government of Southern Sudan is in the process of standing up a taskforce to serve as the coordinating mechanism within GoSS charged with preparing for the referendum and its aftermath. The GoSS deserves credit for mobilizing resources and centralizing its approach to preparations for 2011 and beyond. The international community, particularly the Obama administration, should signal its support of this effort by immediately channeling technical assistance to the taskforce’s working groups, each of which will focus on different aspects of pre- and postreferendum planning.

[23] Interview with UNMIS official, Juba, January 2010.

[24] See “Lord’s Resistance Army Finds Safe Haven in Darfur,” Enough press release, March 10, 2010.

[25] Joint NGO Briefing Paper authored by Oxfam International, “Rescuing the Peace in Southern Sudan” (2010), available at http://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/rescuing-peace-southern-sudan.pdf.

[26] Sudan Tribune, “Sudanese NCP official criticizes referendum law as ‘recipe for war,’” January 5, 2010, available at http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article33679 (Last accessed March 2, 2010).