At present, the only system that the exporters use to avoid buying conflict minerals is verbal assurance: they simply ask, “Did you get this from a conflict area?”

Increasing pressure on electronics companies to ensure that their products do not contain illicit minerals from the killing fields in eastern Congo is beginning to have a significant impact. With bills on conflict minerals moving through Congress, the electronics industry has spent about $2 million per month lobbying Senate offices to relax the legislation, which would increase transparency in the supply chains for tin, tantalum, and tungsten, or the 3Ts.[1]

These mineral ores, as well as gold, are key elements of electronics products including cell phones and personal computers, and also are the principal source of revenue for armed groups and military units that prey on civilians in eastern Congo. Congo’s mineral wealth did not spark the conflict in eastern Congo, but war profiteering has become the fuel that keeps the region aflame and lies beneath the surface of major regional tensions.[2]

Source: Grassroots Reconciliation Group / Sasha Lezhnev

STEP 1: THE MINES

A Gold Rush with Guns

Kaniola gold mine, South Kivu.

Source: Grassroots Reconciliation Group / Sasha Lezhnev

“This region [eastern Congo] has so much of this coltan, you just dig on any hill and you find it.” -Denis, miner, Bukavu, South Kivu

“When the FDLR come to a mine, the first thing they do is get the girls and abuse them. Then they force many people to work and kill those who don’t want to work.” -Jacques, former militia commander, Nyangezi, South Kivu

The journey of a conflict mineral begins at one of eastern Congo’s many mines.[4] A recent mapping exercise by the International Peace Information Service, or IPIS, identified 13 major mines and approximately 200 total mines in the region.[5] Many geologists and companies believe that there may be a much greater abundance of minerals below the surface in eastern Congo, but decades of war have precluded large-scale geological exploration.

CBS’ 60 Minutes highlighted Congo’s deadly trade of gold.

STEP 2: TRADING HOUSES

Looking the Other Way

Mineral trading house in Bukavu, South Kivu.

Source: Grassroots Reconciliation Group / Sasha Lezhnev

Minerals dealer: “Look, this cassiterite [tin ore] is from one mine, and this on the right is from another mine.”

Government inspector: “Yes, and this one is from Shabunda, in the area where the FDLR is.”

-Dialogue at a minerals trading house, Bukavu

From the mines, the minerals get transported to trading towns and then on to the two major cities in the region, Bukavu and Goma. For the gold trade, Butembo and Uvira are also key trading hubs.

A minerals dealer compares tin ore from a rebel-held mine and a government-controlled mine. Source: Grassroots Reconciliation Group / Sasha Lezhnev

STEP 3: THE EXPORTERS

Minerals Enter International Markets

An exporter cited by UN experts as purchasing minerals from the FDLR.

Source: Grassroots Reconciliation Group / Sasha Lezhnev

“The comptoirs [exporters] ask us if we buy minerals from the FDLR, but it’s easy to lie and get around that. They don’t check.” -Thomas, trader, Bukavu

Export companies then buy minerals from the trading houses and transporters, process the minerals using machinery, and then sell them to foreign buyers. These companies, known locally as comptoirs, are required to register with the government, and there are currently 17 exporters based in Bukavu and 24 based in Goma. Just as the exporters provide financing to their suppliers, the majority of them are paid in advance for their minerals by international traders from Belgium, Malaysia, and other foreign countries.

STEP 4: TRANSIT COUNTRIES

Origins Obscured

Gold powder is tested and weighed within dealerships.

Source: Grassroots Reconciliation Group / Sasha Lezhnev

“The border patrols don’t check when you come across from Congo. Then you sell at one of two houses here [in Uganda]. They never ask for papers about where the gold comes from. Then they sell to Dubai. This business is very big, millions of dollars.” -Frank, former minerals smuggler, Kampala, Uganda

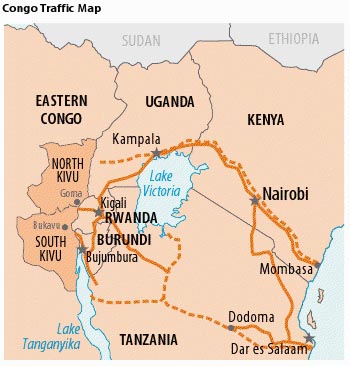

From the exporter the minerals are sent mainly by road, boat, or plane to the neighboring countries of Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi.[10] Some minerals are legally exported, with taxes paid to the Congolese government, while others are smuggled across Congo’s porous borders. Either way, conflict minerals form a major portion of the trade.

STEP 5: THE REFINERS

Minerals to Metals

Inside a tin smelter.

Source: AP Photo / Dado Galdieri

“Minerals used to create the metals in electronics products are often mixed from various sources and exchanged in ways that prevent tracing.” –Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition statement on minerals used in electronics products.

In order for the minerals to be sold on the world market, they have to be refined into metals by metal processing companies.[13] These companies, based mainly in East Asia, take the Congolese minerals and smelt or chemically process them together with metals from other countries in large furnaces.[14]

STEP 6: ELECTRONICS COMPANIES

Conflict Minerals in your Phone

Tin solder is used to affix components to circuit boards.

Source: flickr.com / quapan

“I hear these minerals are used in mobile phones, but I don’t know how. Why don’t the big companies make sure they are not buying from the FDLR? They have that power and money, surely.” –Robert, youth civil society activist, Bukavu

Finally, the refiners sell Congo’s minerals onto the electronics companies. The electronics industry is the single largest consumer of the minerals from eastern Congo. The now-processed metals usually go through a few sub-stages here—first to circuit board and computer chip manufacturers, then to cell phone and other electronics manufacturers, and finally to the mainstream electronics companies such as Intel, Apple, Nokia, Hewlett Packard, Nintendo, etc. These companies then make the products that we all know and buy—cell phones, portable music players, video games, and laptop computers. Because companies do not currently have a system to trace, audit, and certify where their materials come from, all cell phones and laptops may contain conflict minerals from Congo.

CBS’ 60 Minutes highlighted Congo’s deadly trade of gold.

Steps Toward a Solution

- Trace: Companies must determine the precise sources of their minerals. We should support efforts to develop rigorous means of ensuring that the origin and production volume of minerals are transparent.

- Audit: Companies should conduct detailed examinations of their mineral supply chains to ensure that taxes are legally and transparently paid to the Congolese government and guard against bribery and fraudulent payments. Credible third parties should conduct or verify these audits.

- Certify: For consumers to be able to purchase conflict-free electronics made with Congolese minerals, a certification scheme that builds upon the lessons of the Kimberley Process will be required. Donor governments and industry should provide financial and technical assistance to galvanize this process.

What You Can Do:

- Call, email, or meet with your Senators and urge them to both cosponsor and help strengthen the Congo Conflict Minerals Act of 2009 (S.891). Talking points can be found at www.raisehopeforcongo.org or you can dial the U.S. Capitol switchboard at (202) 224-3121.

- Help us increase demand for conflict-free electronics. Visit www.raisehopeforcongo.org to email the biggest buyers of Congo’s conflict minerals—major electronics companies—and let them know that you want to buy conflict-free products. The message is clear: “If you take conflict out of your cell phone, I will buy it.”

- Stay in touch! Text the word “Congo” to 228488 (spells ACTIV8) to get updates and actions from RAISE Hope for Congo.

Appendix A: What Should Be Done About Congo’s Gold Trade?

Author: David Sullivan

CBS’ 60 Minutes highlighted the deadly trade of gold from the mines of Congo. Enough experts detail how to track the supply chain of conflict gold, and how you can ensure your jewelry is conflict-free.

Miners bring gold powder to gold dealerships, where it is weighed and tested.

Source: Grassroots Reconciliation Group / Sasha Lezhnev

Concerted consumer action has enormous potential

to clean up these supply chains.

A powerful segment on CBS’ 60 Minutes demonstrated with stark clarity how the trade in conflict gold is a major source of funding for armed groups that target civilian populations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Gold also plays a key role in electronic devices, making up two-thirds of value of the metals inside cell phones and personal computers. A jewelry industry spokesperson interviewed for the show seemed genuinely perplexed about how to ensure that gold does not finance the conflict in eastern Congo. Yet the supply chain in gold can be made conflict-free through the same three steps that Enough has recommended for other conflict minerals:

1) Trace: Companies must determine the precise sources of their minerals.

2) Audit: Companies should conduct detailed examinations of their mineral supply chains. Credible third parties should conduct and/or verify these audits.

3) Certify: In order for consumers to be able to purchase conflict-free electronics and jewelry made with Congolese minerals, a certification scheme that builds upon the lessons of the Kimberley Process will be required.

The gold trade differs from that of other minerals in several important ways:

• Gold is much more valuable by weight compared with other minerals. As a result, it is easier to smuggle small amounts of gold that are valuable.

• Gold is easier to refine than the other minerals and can be smelted into metal earlier in the supply chain, making it more difficult to trace.

• Because of gold’s importance as a store of value in the international financial system, legislative efforts to curb the import of gold into the United States are more complicated than in the case of other minerals.

These complications do not mean that that a transparent supply chain is impossible, but consumers will have to generate sufficient pressure on the industry to take the necessary action. Because more than 80 percent of gold in the United States is used in jewelry, and nine percent of worldwide gold is used in electronics, concerted consumer action has enormous potential to clean up these supply chains.

How does U.S. legislation address Congo’s gold trade?

Gold is cited as a source of financing for armed groups in eastern Congo in both the Senate (S.891) and House (H.R. 4128) versions of legislation on conflict minerals. But because of the complicating factors described above, gold has not been included in the sections of the legislation that mandate more traceable and transparent supply chains. However other critical aspects of legislation, including a U.S. government strategy to address this issue, the mapping of militarized mining sites, and ensuring that State Department human rights reports cover the issues related to the trade in conflict minerals, do incorporate coverage of the gold trade.

Can I buy conflict-free jewelry?

The No Dirty Gold campaign is an effort to end destructive impacts of gold mining, including the sourcing of gold from conflict areas, such as eastern Congo. A list of retailers that have signed on to support their 10 Golden rules is available here.

Tiffany & Co.: According to their website: “The majority of the gold and silver used in Tiffany & Co. jewelry workshops is obtained from a single U.S. mine that meets high

standards of social and environmental responsibility.”

Wal-Mart: Wal-Mart’s Love Earth jewelry line is a completely traceable line of jewelry that allows consumers to trace the supply chain for their jewelry online, back to specific mines of origin. However this is only one line of products, and Wal-Mart’s current target is to make 10 percent of its diamonds, gold, and silver traceable by 2010.

Fair Trade Gold: The Alliance for Responsible Mining, or ARM, has pioneered a set of standards for fair trade artisanal gold. For more on this effort, visit their website.